Overview

Tony Chakar seems to be an urban planning specialist in a world full of experts ... and cities. When human communities exceed a certain limit, they create a special space governed by rules that differ from what human beings are used to up to now: The Metropole. Tony Chakar's work stems from this space, its presence anywhere else is impossible. It can only exist where desire roams in a space of adventure and emotion.

The work of Art:

the size and nature of the texts in Chakar's works create a bewilderment in the viewer who is used to categorization and understanding. Why does he present his works as works of art or installation, not as works of literature even in an original image? Is it enough to have a photo or a statue to assume that it is a "work of art" and that the text is only a comment? To transfer the text from the state of writing to the state of "work of art" the answer is definitely negative. However, these legitimate questions lead to certain comments that relate to the nature of the relation between the words in his text and the other components of his work and to the work itself: its medium, its vehicle and its movement.

What is special about Chakar's works is how he translates his texts from one language to another. He is not worried about the language or the style, which does not mean their absence. As Bart says, they cannot be absent from the act of writing and the writer cannot control them. What might be abs~nt is the traditional relation to writing, "literature" and language in its third dimension, in its social goal. The question should be not "what" these texts address, but whom they are addressed to.

There are few obvious signs of a second person (like in the footnotes), but these are signs Imposed by the nature of the language and its rules that require a subject to act and an object to hear. On a deeper level, these texts do not assume a reader is equipped with a prior methodology and knowledge, and it does not equip that reader either.

Sometimes, and only by pure coincidence, it might meet one who is "distracted", but it only pays attention to the components of the work themselves: the photos, the painting, the map, etc.

Walter Benjamin realizes that the photograph's job is similar to that of the detectives'. That's why one should respect the captions or what the papers have written on it, for the explanations unite and become an aspect that convinces instead of being a reason to analyze. In this framework, it is clear that understanding a photo, even without a comment, is impossible unless one goes back to language components preceding it. The seriousness of Chakar's work lies precisely in this idea. The text is not an independent work. The text is not a title. The text is not a comment. It cannot be isolated. It cannot imply or unite.

Chakar's text seems to be a speech. It is a moment taken out of an uncut conversation between visual-cultural units (the female statue for example or the map), and spatio-linguistic or acoustic metropolis units (the spectacle the story as we shall see later). These units collide in the universe of the metropolis. This dialogue constitutes the substance for Chakar's work of art. Thus it is impossible to exist outside a certain space.

Once the substance is distinguished from the vehicle, and precisely through this vehicle that the viewer enters back into the work of art and its adventures. The special relation among the components of the work does not allow any of them to be the vehicle of the work and eliminates the chronological relations among them.

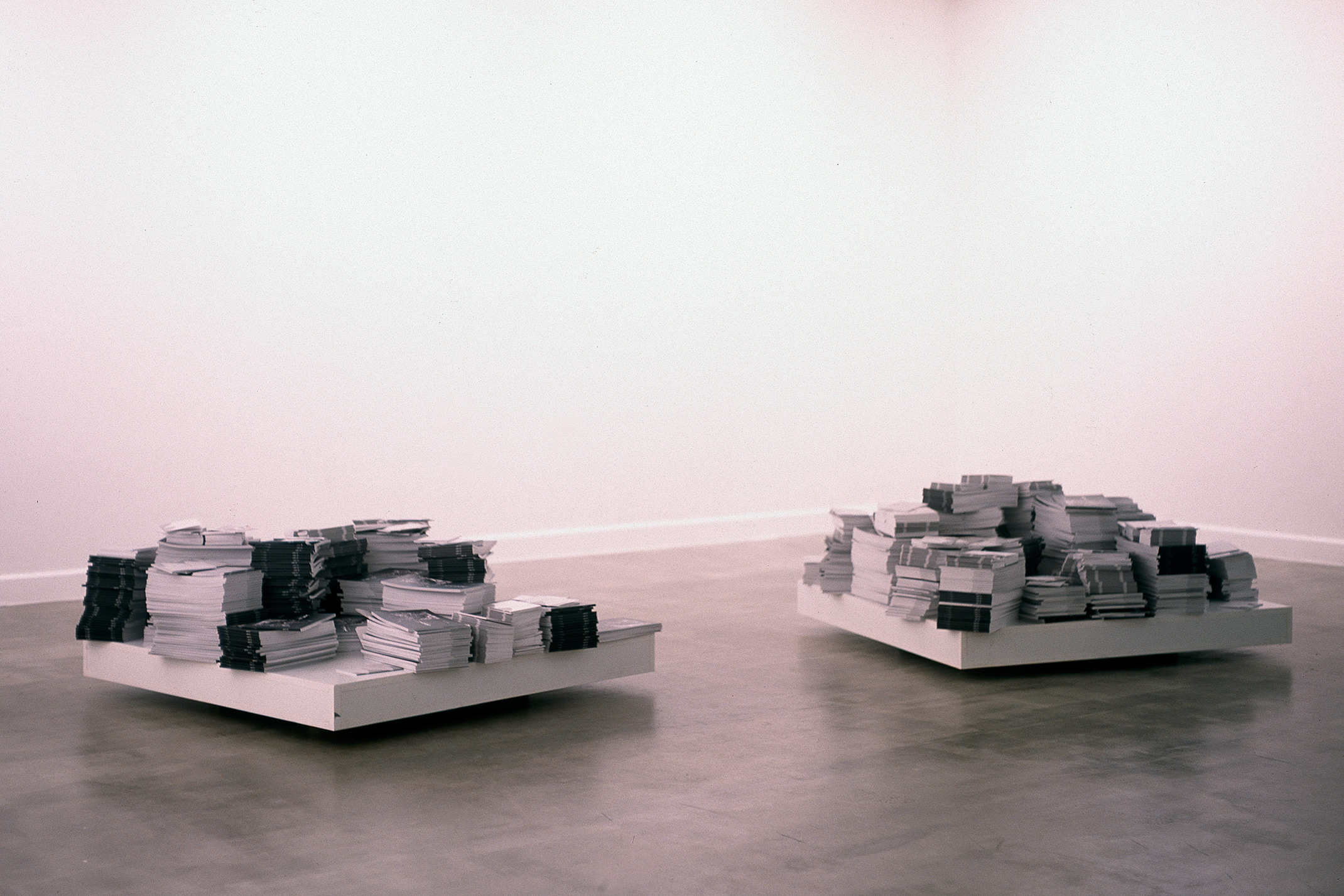

The definition of this work then requires that these components work to make the vehicle's movement in the metropole space difficult. The vehicle of the work of art according to Chakar is always a spectacle (the spectacle is not a photo, but a story). The spectacle of the street or the spectacle of the artist or the spectacle of the city's perception of time. The work itself is an objecting movement (literally) in a space.

Space: the scene - the story:

Chakar reads the city as a viewer (like Koolhaas), but he builds it. The spectacle is not the image

of anything, but its story, as Chakar realizes in Ashrafieh. The truth is that the spectacle and the story are not of different natures, that is, one's space is made of hearing before seeing, and one's country is nothing but the familiarity of voices. Through the story, even if it's untold, through the voices, the city is printed on the body of the passer by, the distracted, not the analyst. Thus, Chakar builds his spectacles instead of telling them. The other cannot understand (a letter to Tim Ettchels), and because it is Chakar's own private story and he asserts this privacy. Spending or giving away does not confirm possession, because the story is the "uniqueness" of the spectacle. possession here can only be confirmed through pretending to be rich, through building its space, through adventure.

The Adventure: the Work is Space:

"All the things I see will live after me", Akhmatova says. "Oh, but in what state would it be?" is Chakar's hidden answer. He never gets tired of looking for time's action in the city. ("I was standing in the present looking towards the past, but between me and the past there was a prism that deformed my view and rendered all attempts to reconstitute a lost loved one, and hence to reconcile with that past, futile.") and the city people (the city overloaded with death) he does not get tired of observing them in things.

The act of time fills the relation to things, so Chakar tries to make it enter his space without rendering it rigid or dead. This also applies to poems, news; signs to Beirut and Paris do not create rigid masks, but enter his space due to the act of time. If we realize that the map precedes the world, things appear in Chakar's space as bits that used to belong to a map the size of the world. Its relationships explode, it regains the spectacles in their brilliance, it returns adventurouS, it reveals that adventure and desire are one and the same, their time does not unfold its end, because Tony Chakar's compassion and tenderness alone restructures them into a space that appears as a space for a new promise. Fadi Abdullah

Related Content

Sharjah Biennial 6

Sharjah Biennial 6