Images

All images are courtesy of AMAR Foundation

search

All images are courtesy of AMAR Foundation

Al-Qaṣīda ‘Alā Al-Waḥda

The Arab Music Archiving and Research Foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents Nidhamona Al Musiqqi.

Al-qaṣīda ‘alā al-waḥda (on-the-beat / 4/4 rhythmic cycle) is a distinctive Nahḍa (Arabic Renaissance) form that appeared in the second half of the 19th century. This does not imply that pre — Nahḍa performers did not sing Arabic qaṣā’id to the waḥda — or to any other — rhythmic cycle. Al-qaṣīda ‘alā al-waḥda was intended to blend the Sufi form (i.e. the dhikr) and the secular form. The rhythmic cycle was used in the inshād of qaṣā’id (chanting of qaṣā’id) in order to preserve the group approach to the responsorial parts — i.e. al-inshād (the singing/chanting) and al-radd (the répons) — in dhikr ceremonies. But later on the takht (Arabic orchestra/ensemble) was entered into this minimalistic Sufi form that was then performed with the instrumental and vocal lāzima (chorus): Sufi music and secular music came together, creating a form equivalent to other revamped forms, such as the dawr and the taḥmīla…etc. Here’s a detailed description.

According to Professor Nidaa Abou Mrad, the qaṣīda ‘alā al-waḥda is the result of a fusion between two major forms in the eastern traditions: al-tilāwa (cantillation/recitation) and al-lāzima (chorus).

The meaning of al-tilāwa in this context is the tilāwa form or the singing form of a qaṣīda mursala (of non-metric measure), i.e. the improvisation of a melody for a classical Arabic text outside any rhythmic cycle.

Here is an example of a qaṣīda mursala performed by Sheikh Alī Maḥmūd.

Al-lāzima is a chorus or a madhhab, a melodic phrase repeated after specific vocal or instrumental passages. In the 20th century, al-lāzima was the instrumental phrase linking two melodic passages of a song or of an instrumental piece.

In the qaṣīda ‘alā al-waḥda, the lāzima implies Lāzimat el-‘awādhil adapted from a madhhab in the dawr Āh yā anā to the sīkah maqām (mode), and whose existence’s only proof is its mentioning in Nahḍa books. The lyrics of this dawr are: 'Āh yā anā w-ēsh li-el -‘awādhil ‘andinā, qūm maḍya‘ el-‘udhdhāl we-wāṣelnī anā'. Lāzimat el-‘awā” hil can be performed to the waḥda rhythmic cycle and to different maqāmāt according to the performer’s wish.

Let us listen to a performance of Lāzimat el-‘awādhil by a baṭāna — choir of munshidīn (chanters) — to the bayyātī maqām, the most common in qaṣā’id chanting.

The fusion between the two above mentioned factors (tilāwa and lāzima) created a new form: the qaṣīda ‘alá al-waḥda. This form was the principal competitor of the dawr, especially as to the conclusion of the waṣla.

According to Professor Frédéric Lagrange, the tilāwa of the qaṣīda accompanied by instrumental music is an invention particular to the Nahḍa period. He adds that the improvisation of a qaṣīda ‘alá al-waḥda is a marriage between the rhythm of the lyrics and the cyclic rhythm, half — composed, in which the performer renders different versions where the rhythm of the lyrics may follow the cycle’s rhythm or the other way around, with every verse ending with a dum.

‘Abduh al-Ḥamūlī was in the lead of those who performed qaṣā’id ‘alá al-waḥda in their early stage at the end of the 19th century, followed by Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī, ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī, Salāma Ḥigāzī and many others. During this period, Lāzimat el-‘awādhil was clearly the chosen introduction to the qaṣīda, the chosen chorus after specific transitions, and the chosen conclusion ending the tilāwa of the verses. During that founding phase, the improvisation of the qaṣīda was limited to 5 maqāmāt: rāst, bayyātī, sīkāh, ṣabā and ḥijāz. The ‘ushshāq and the jahārkāh followed at the beginning of the 20th century. Let us listen to the qaṣīda Alā fī sabīl el-llāh to the bayyātī maqām performed by Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī and recorded by Sama‘ al-mulūk — daughter company of Bekka Records — in 1905 on one side of a 27cm record #1257. Note that the recording was cut because the duration allowed by the record ended before Sheikh Yūsuf could resume his conclusion starting with Āh yā anā, as this was the first qaṣīda recorded by Sheikh Abū l-Ḥajjāj (Manialawi) who was new to recording.

Later on, Abū al-‘Ulā Muḥammad brought some new additions to it. He minimized the role of Lāzimat el-‘awādhil in favor of the ‘Arūḍ and used it as a simple introductory instrumental piece, sometimes totally ignoring it in maqāmāt. He also used derived maqāmāt such as nahawand, ḥijāz kār and suznak rāst…etc. This phase marked the start of the trend towards setting a global frame for melodic phrases.

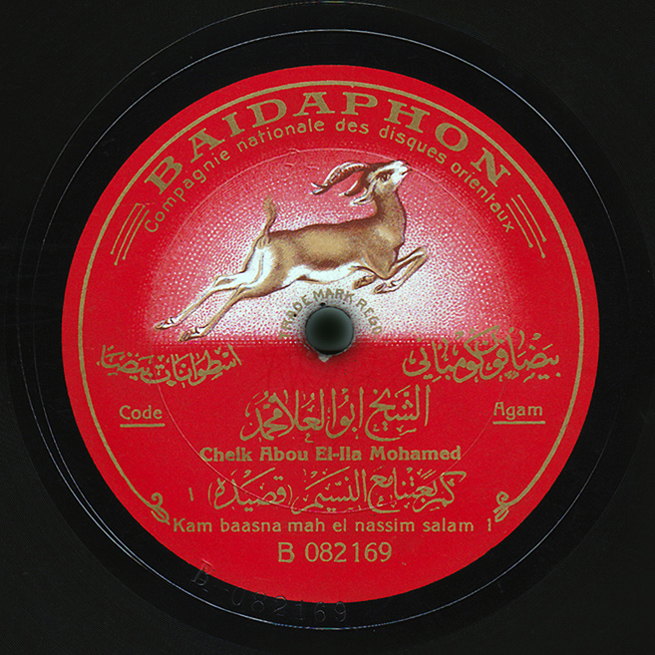

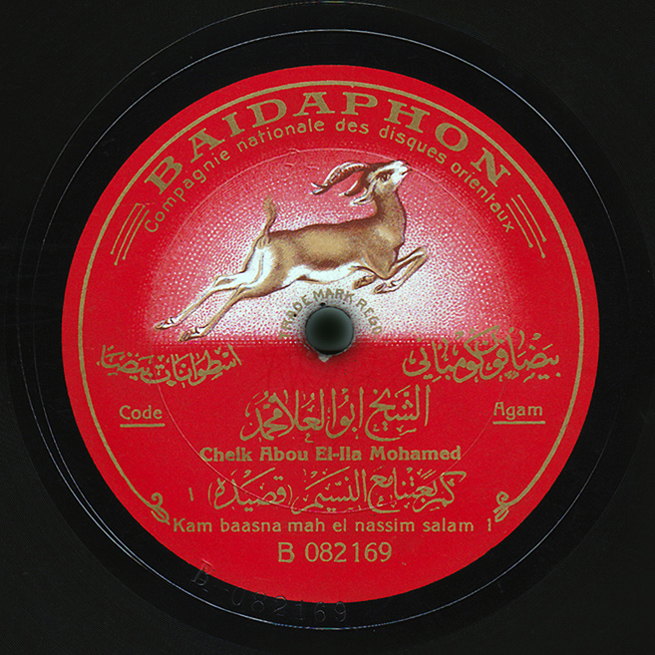

Let us listen to Sheikh Abū al-‘Ulā Muḥammad singing the qaṣīda Kam ba‘aṯnā ma‘ al-nasīm to the rāst maqām. Many other performers sang it after him, following the same melodic frame. This performance was recorded by Baidaphon around year 1921, on both sides of a 27cm record #B-082169 and #B-082170.

During these two phases, the role of the takht (accompanying instrumental ensemble) in chanting the qaṣīda ‘alā al-waḥda was to shadow the singer (murāsala) while the latter improvised the verses. It also consisted in muḥāsaba, to respond with concise instrumental structures derived from the phrases he sang. The takht‘s role changed during the following phase that addressed the full setting of vocal phrases accompanied by the composition of introductions and of some internal elements. Their role was thus to perform strictly according to the composer’s will. An example illustrating this phase is the qaṣīda Yā nā‘iman raqadat gufūnuh written by Aḥmad Shawqī, composed and performed by Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Wahāb. Yet, ‘Abd al-Wahāb adorned it with a wide variety of improvised elements despite the set melody. He recorded it in 1932 with Baidaphon on both sides of an electrical power-printed 25cm record #B-095364 - #B-095366.

After this period, and apart from rare exceptions, the qaṣīda ‘alā al-waḥda was dropped, and singing in classical Arabic was included in the vocal forms starting the mid 1900s. The composition of a qaṣīda then followed the ṭaqṭūqa’s, the monologue’s or any other composition form existing at that time.

Thank you for listening.

This episode was brought to you by Ghassān Saḥḥab and Muṣṭafa Sa‘īd.