Images

All images are courtesy of AMAR Foundation

search

All images are courtesy of AMAR Foundation

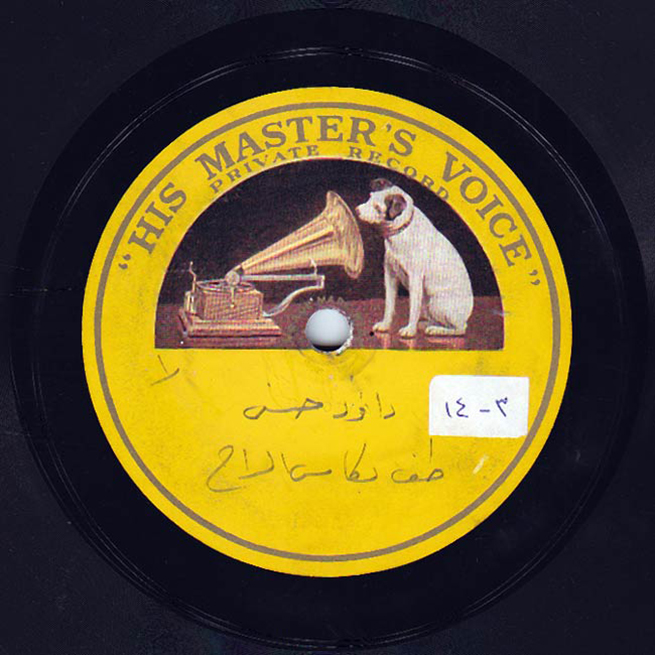

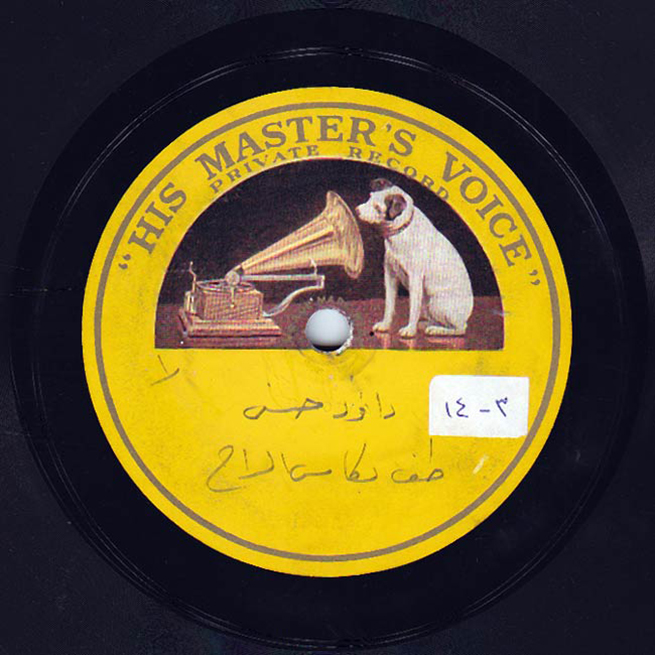

Dāwūd Ḥusnī (4)

The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents Min al-Tārīkh.

Dear listeners, welcome to a new episode of Min al-Tārīkh.

Today, we will be resuming our discussion about Dāwūd Afandī Ḥusnī with Prof. Frédéric Lagrange.

There is a difference between Dāwūd Ḥusnī and Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī:

Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī specialized exclusively in dawr;

While, as we already mentioned, Dāwūd Ḥusnī’s musical production included light forms such as ṭaqṭūqa and theatre tunes besides the dawr.

Let us start with the ṭaqṭūqa:

What is the difference between the earliest ṭaqṭūqa recorded in the early 20th century, and the ṭaqṭūqa during its commercial phase that started almost right after WW1 and reached its peak in the mid-1920’s, then evolved again with Zakariyyā Aḥmad until it became the seed of what would later be called ughniya.

How did Dāwūd Ḥusnī, and his generation, i.e. the early 1920’s composers such as Al-Qaṣṣabjī, contribute to its development?

The difference may lie in the following:

The earliest 20th century ṭaqṭūqa, that consisted in a single melodic phrase or two at most, first evolved with regards to the vocal range used to sing it: it was not limited anymore to one jins and was now sung to a maqām, i.e. two or three jins, which implies a wider vocal range and a variety of musical phrases.

However, there was still a specific melody, one or two melodic phrases in the madhhab, and four or five ghuṣn to the same melody (no change from one ghuṣn to the other). Thus, the form remained that of the 'traditional' ṭaqṭūqa, i.e. the 1920‘s ṭaqṭūqa, not the earliest ṭaqṭūqa.

These beautiful ṭaqṭūqa include Sēd el-‘Aṣārī, and Hatīlī yammā ‘aṣfūrī that was recorded by both Zakī Murād and Sāmī al-Shawwā, in two beautiful performances.

This is true.

(♩)

Another ṭaqṭūqa became famous because it was among those performed by major bands such as ‘Abd al-Ḥalīm Nuwayra’s band… But I suggest we stay as far as possible from it.

Some songs in the 1970’s and 1960’s were just made to satisfy the demand for old tunes, such as Amar luh layālī, Yamāma ḥilwa, etc…

Exactly.

Concerning ṭaqṭūqa Amar luh layālī that you just mentioned, Farīd al-Maṣrī, an unknown muṭrib who recorded very little, gave an original beautiful sober and joyful performance of it…

(♩)

Along with the male voices who interpreted them, there were also many muṭriba such as Umm Kulthūm as well as 'light' singers –this 1920’s generation of Jewish muṭriba such as like Khayriyya al-Saqqā and Sihām– but also Nādira Amīn, Najāt ‘Alī, and probably one of the major muṭriba Layla Murād who started off with Dāwūd Ḥusnī.

Dāwūd Ḥusnī may have played a part in discovering her… He may be the one who introduced her…

She was the daughter of Zakī Murād. They belonged to the same artistic milieu… they knew each other. He had certainly heard her in Zakī Murād’s home.

Of course.,,

Let us listen to a ṭaqṭūqa…

Ḥayrāna lēh.

Ḥayrāna lēh in the voice of Layla Murād. This fantastic ṭaqṭūqa resembles a dawr…

(♩)

We have heard the daughter… We must listen to her father.

Of course… He was her father, yet he still sang El-‘uzūbiyya ṭālit ‘alayya. (I have been single/celibate for too long)

Wasn’t he married at the time?

It does not matter…

Let us listen to the beautiful El-‘uzūbiyya to the ḥiṣār in the voice of Zakī Murād.

(♩)

Let us now talk about the third part of Dāwūd Ḥusnī’s musical compositions: the operettas and the theatre tunes that include duets, choral singing, and the search of expressionism… all these types and musical ornamentations that seem to contradict the spirit of Dāwūd Ḥusnī characterizing his taqsīm and his dawr in particular.

How can one explain that he tried his luck in these diametrically opposed tendencies? …Like Sayyid Darwīsh.

True.

Sayyid Darwīsh was maybe influenced by western expressionism, even in his dawr, such as the āhāt in some of his dawr.

While Dāwūd Ḥusnī kept the improvisation aspect in all his dawr, while the theatre tunes he composed were influenced by the western musical styles related to this form.

Dāwūd Ḥusnī first partnered with Zakī ‘Ukāsha’s band in his first work Ṣabāḥ, then with the band of Munīra al-Mahdiyya for whom he composed the play El-ghandūra that was later made into a movie.

It is Munīra al-Mahdiyya’s only movie, and it is unfortunately lost.

Indeed.

He also partnered with the band of Najīb al-Rīḥānī and Badī‘a Maṣābnī…

…Kish kish bēh.

…Kish kish bēh… In the play Al-layālī al-milāḥ whose songs were authored by Badī‘ Khayrī who also authored Munīra al-Mahdiyya’s songs in El-ghandūra.

We must make a distinction between:

The theatre tunes he composed for the muṭriba — or real voices — such as Munīra al-Mahdiyya and Faṭima Sirrī;

And the melodies he composed for performers with limited vocal abilities such as Badī‘a Maṣābnī, or those with zero vocal abilities such as Najīb al-Rīḥānī — who is similar to Fu’ād al-Muhandis but came 50 or 40 years before him.

Right.

He was funny and pleasant, but his voice was non-existent… One bears no relation to the other…

Let us listen to an excerpt of El-ghandūra and find out what Dāwūd Ḥusnī was thinking about when he composed theatre tunes for Munīra al-Mahdiyya, i.e. when he was not composing a dawr or a ṭaqṭūqa for her.

Munīra al-Mahdiyya the actress.

Exactly… Munīra al-Mahdiyya the actress.

Then, we will listen to Najīb al-Rīḥānī in Al-layālī al-milāḥ.

Ok.

(♩)

Dāwūd Ḥusnī died in silence in 1937.

Some sources state that he embraced Islam before he died while others say that he remained Jewish. Ibrāhīm Murād Barūkh Murād and Zakī Barūkh al-Gamīl’s Internet website I mentioned in the beginning says that he was buried in the Karaite Jewish cemetery in Basātīn in Cairo.

We know for sure that his children from his first marriage remained Jewish, while those from his second marriage embraced Islam — whether he had embraced Islam or his children had. I think his grandchildren or great grandchildren still reside in Egypt…

This is true.

… But he died in silence…

Indeed… And we must give him a chance to let us hear his voice.

His last recordings were made at the 1932 Cairo Congress of Arab Music.

Let us listen to him singing an only and unique dawr that was only recorded by him. The composer may either be Dāwūd Ḥusnī or someone before him.

The structure is solid — like the structure of his dawr —, while the lyrics resemble those of muwashshaḥ because they are in between literary and colloquial Arabic: a muwashshaḥ characteristic.

I think he sings Wa-al-ladhī wallāk malik in the middle of this dawr.

Ṭuf bi-kās el-rāḥ yā hādhā al-gamīl… The language is indeed in between literary and colloquial Arabic.

This 'middle language' characterises muwashshaḥ.

The lyrics of the dawr are closer to colloquial Arabic.

Both languages must not be perceived as independent, but as related poles, and the lyrics would be somewhere within the spectrum linking them.

The strange lyrics of this dawr are closer to literary Arabic, which usually characterizes the lyrics of muwashshaḥ.

The form is that of a dawr that includes henk, and rhythmic transitions that lead us to believe that it was composed by Dāwūd Ḥusnī himself.

The perfect conclusion would be Dāwūd Ḥusnī’s last recording: dawr Ṭuf bi-kās el-rāḥ to the nawrūz rāst recorded in March 1932.

(♩)

The perfect conclusion indeed…

We thank Prof. Sheikh Frédéric Afandī Abū Shōna

(♩)

And we thank Dāwūd Ibn Khiḍr, the jeweller’s son who produced gems his whole life.

He sure did…

Dear listeners,

We will meet again in a new episode of Min al-Tārīkh.

Min al-Tārīkh is brought to you by Mustafa Said.