Images

All images are courtesy of AMAR Foundation

search

All images are courtesy of AMAR Foundation

Dawr El-bulbul gānī

The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents Sama‘

Dawr El-bulbul gānī was composed to the rāst suznak maqām by Ibrāhīm Afandī al-Qabbānī, writer unknown.

(madhhab)

El-bulbul gānī we-allī Ismaḥ bi-waṣlak yā khillī

Fa-ultiluh ib‘id ‘annī El-bulbul ‘a-el-ḥabīb za‘lān

Yāmā inta ẓālim We-el-alb mashghūl bi-el-maḥabba

Wallā inta ‘ālim Lēh kidā za‘lān

Ana min gharām maḥbūbī Ṭūl el-lēl sahrān

Min gharāmak ‘āshi’ gamālak El-bulbul ‘ala el-ḥabīb farḥan

(dawr):

Lēh yā ḥamām bi-tnawwaḥ lēh Fakkartinī bi-el-ḥabāyib

Yā hal tara nirga‘ el-awṭān Wallā n‘īsh el-‘umr gharāyib

Yāmā inta ẓālim

During this episode, we will analyse and compare two recordings of this dawr.

One recording is by Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī — excerpted from the Complete Works of Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī published by AMAR in October 2011 — whose performance of this dawr is famous. It was recorded by Gramophone in 1909 on four 30cm record sides, order # 012427, 012428, 012429, and 012430, matrix # 1714 C, 1715 C, 1716 C, and 1717 C.

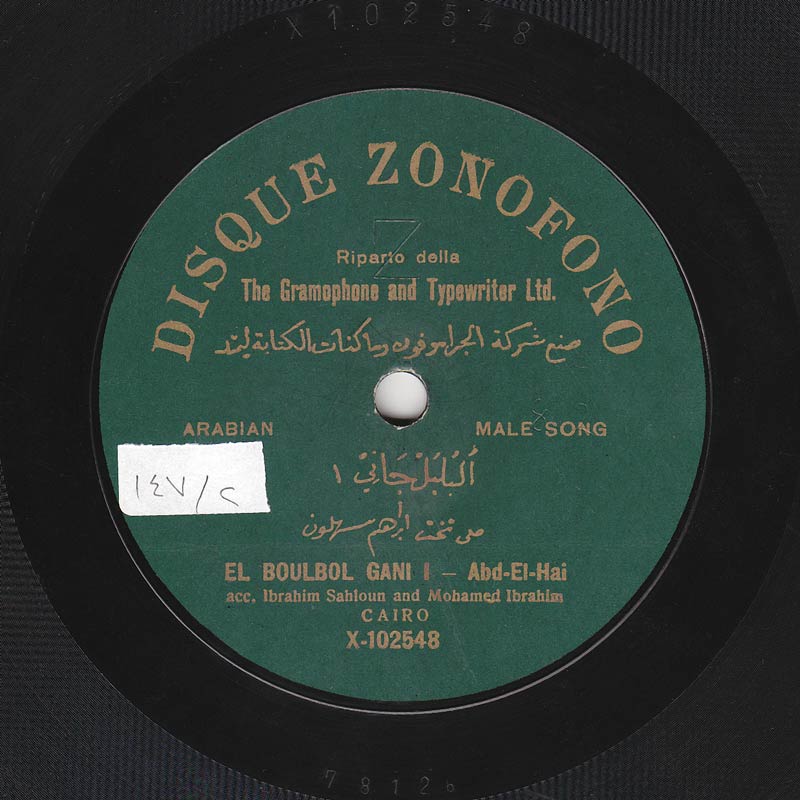

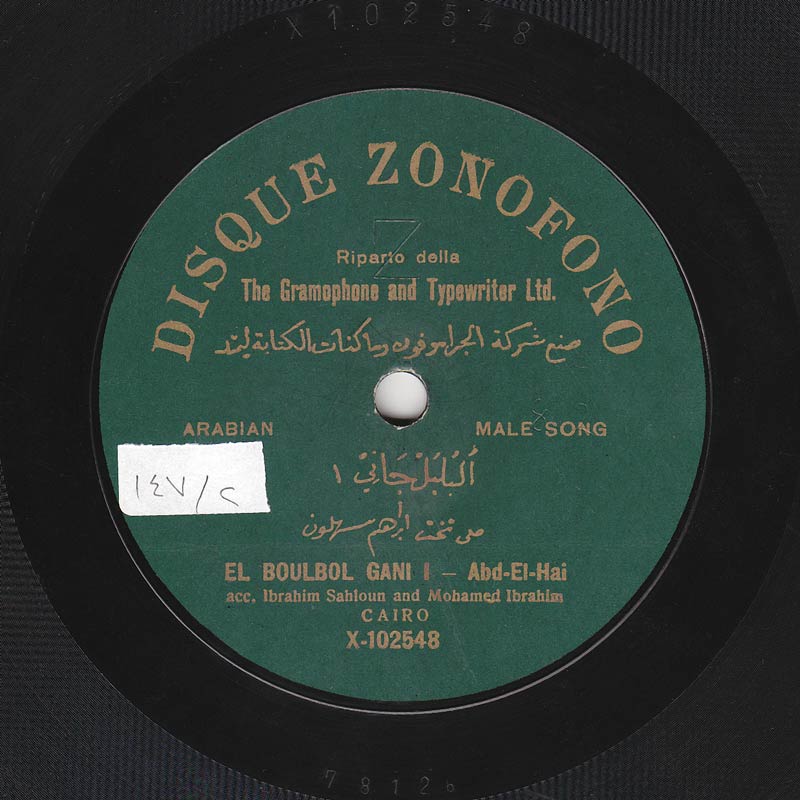

The other recording is by ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Afandī Ḥilmī made by Zonophone — under Gramophone — three years before the above mentioned record, on three 25cm record sides, order # X-102548, X-102549, and X-102550, matrix # 7812 B, 1/2 B, and 1/3 B.

Let us start our analysis.

Dawr El-bulbul gānī was one of the most widespread adwār at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th, performed and recorded numerous times. It is said that Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī was paid 20 Egyptian Pounds more than his usual fee when he sang it.

Dawr El-bulbul gānī was also one of the most important satiric stops in the mid 1950s movies regarding Classical Arabic Music — or as I like to call it the Literary Arabic Music. They used to deliver the sentence 'El-bulbul za‘lān lēh' and declare with sarcasm that Classical Arabic Music was full of sadness, lamenting and crying. It is a matter of opinion. We will not tackle the issue of mockeries in the mid 1950s. We may, or may not, discuss this issue later on.

Dawr El-bulbul gānī was famous in different milieus: among the listeners as a major dawr composed in the late 19th century; in the popular milieu; and it was recorded by the mazāmīr band.

It seems that this dawr is the origin of the famous rāst taḥmīla.

Kāmil al-Khula‘ī said that he conducted a research to determine its poetry and musical rhythmic pattern, but found none.

Some said the melody was composed first and the lyrics were written and added later by the composer Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī himself. Some mentioned the names of other lyricists. Others said that this dawr was created for a political purpose after the British Forces occupied Egypt in 1882, and Aḥmad ‘Urābī and Maḥmūd Sāmī al-Bārudī were exiled, and after what happened to ‘Abdallāh al-Nadīm… etc.

Anyway, regardless of all these stories, today’s episode is dedicated to two recordings of this dawr:

The first recording is by ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī, made by Zonophone in 1906 probably.

The second recording is by Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī — who recorded the dawr three times:

The 1st time in 1905 with Sama‘ al-Mulūk,

The 2nd time in 1907 with Gramophone,

The 3rd time in 1909 with Gramophone again.

Though, the recording we will analyse today is the one made in 1909 because it honestly is the most mature of all these recordings.

In 1905, Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī recorded the dawr with Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād (qānūn), maybe Aḥmad al-Laythī or Manṣūr ‘Awaḍ (‘ūd), and ‘Alī ‘Abduh Ṣāliḥ (nāy).

In 1907, he recorded the dawr with the takht that accompanied him in the Gramophone recordings, including Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād, ‘Alī ‘Abduh Ṣāliḥ, and Ibrāhīm Sahlūn.

In 1909, he recorded the dawr again with Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād and ‘Alī ‘Abduh Ṣāliḥ, but this time with Sāmī al-Shawwā playing the violin instead of Ibrāhīm Sahlūn.

The dawr was composed by Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī to the rāst maqām, suznak sub-maqām.

Let us listen to ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī’s version of the madhhab, then to Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī’s.

(♩)

We have listened to ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī singing, accompanied only by Ibrāhīm Sahlūn (kamān) and Muḥammad Ibrāhīm (qānūn).

Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī sings accompanied by the three musicians listed earlier, with noticeable percussions by Muḥammad Abū Kāmil al-Raqqāq — actually more noticeable than in other works. The percussions in Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī 1909 recordings were more apparent than in the recordings made earlier. I think the result of the technological advance that took place between 1906 and 1909 is very clear to our listeners.

The madhhab shows that ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī sings dawr El-bulbul gānī as he would sing any ordinary and unexceptional dawr.

Whereas Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī deals with it differently, demonstrating great harmony with his band born from thorough experience. For example: when he repeated 'El-bulbul gānī', there was a lāzima, and when he wanted to shift to Fa-ultiluh ib‘id ‘annī, the lāzima changed. It is obvious that they had rehearsed a lot together and sang the dawr hundreds of times. Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī’s biṭāna had memorized the moment he started and stopped singing, which clearly shows the experience they had in working together. It is also clear that they knew the duration of each section. Listening to the recording of the complete work will clarify this.

We have finished discussing the madhhab.

Let us now go the tafrīd, and discuss the changed text following the fixed one, and note the way each of these two performers deals with it.

We will notice that ‘Abd al-Ḥayy deals with it as with any ordinary dawr, while Sheikh Yūsuf deals with it in an exceptional way. He talks like the bird, then like the pigeon in the tree twittering bi-tnawwaḥ lēh?

Let us listen to bi-tnawwaḥ lēh performed by ‘Abd al-Ḥayy, and performed by Sheikh Yūsuf. We will discuss them right after.

(♩)

We have heard ‘Abd al-Ḥayy dealing with it as with an ordinary dawr. Note the hint of sadness — also present in his performance of many adwār — that leads us to relive the feeling of weakness and misery, and maybe revives what was said about this dawr having a political meaning after the 1882 defeat.

Sheikh Yūsuf sounds full of hope, singing happily and joyfully, singing and twittering like the bird in the tree. According to him, life will be beautiful and the crisis will pass… all the pleasant and happy hopefulness we always feel when listening to Sheikh Yūsuf.

Let us now look at the issues of taṭrīb, ta‘bīr (expression), and terminology. I honestly can’t understand this issue even though we have studied in academies 'harmony', 'contrapoint' 'polyphony', and all western styles, 'musicology' and all that is taught in academies. Yet none of the latter and no methodology convinced me that there is a difference between taṭrīb and ta‘bīr. Ta‘bīr is taṭrīb, and the other way around. When I say 'Allāh' and 'Yā salām', this is a ta‘bīr because it expresses/conveys a state. I honestly do not understand the ta‘bīr or taṭrīb logic. I really can’t. Here for example, when Sheikh Yūsuf talks like the bird, is it ta‘bīr or taṭrīb? When ‘Abd al-Ḥayy expresses sadness, is it ta‘bīr or taṭrīb? I honestly can’t answer this question.

Let us go back again to the musical analysis.

After the tafrīd, we must reach a section comprising a dialogue between the munshid and the biṭāna.

In order to reach this part, there are two processes:

Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī shifts many times until he reaches the original dialogue with the sentence 'za‘lān lēh' between the munshid and the biṭāna;

‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī’s route is much shorter as he shifts from the fifth scale directly to the bayyātī, without going through stages.

After Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī finishes the tafrīd, the instrumental band takes him to the bayyātī from the second scale, i.e. from the rāst to the dūkāh. It is obvious that the band is conducted by Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād.

Let us listen to the interpretation of the phrase we have listened to, performed by Sāmī al-Shawwā — who was just beginning his career as a musician at the time —, and note the way he tries to sing and talk to Sheikh Yūsuf with his violin. Let us listen to this interpretation, then to the shift to the bayyātī from the second scale.

(♩)

After this shift, Sheikh Yūsuf continues with the bayyātī for a short while then conducts the shift to the sīkāh, i.e. the third scale (we said rāst, dūkāh, sīkāh). He conducts the shift to the sīkāh himself, the band does not. This is strange. Why did he choose for the band to shift to the dūkāh, but shifted himself to the sīkāh. I do not know. There is no explanation.

(♩)

We have noticed how Sheikh Yūsuf shifted to the second scale, then to the third. He will shift now to the fifth scale step, ḥijāz, then to the bayyātī from the fifth.

‘Abd al-Ḥayy shifts directly from the rāst to the bayyātī, from the fifth scale step, and also sings 'za‘lān lēh' to the ṣabā fifth scale step. The sadness continues in a very direct manner.

Sheikh Yūsuf follows the ḥijāz then shifts to the bayyātī. He chooses a path including lamenting of course, but also hope. There is also a paternal aspect: 'inta za‘lān lēh?' (why are you sad?) …Tomorrow things will look better… . Opposite to the sadness and despair in ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī’s interpretation.

Let us listen to the biṭāna’s dialogue between both sides with Sheikh Yūsuf, and with ‘Abd al-Ḥayy.

Sheikh Yūsuf’s biṭāna is larger and includes a qarār element (bass) that enters suddenly.

‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī’s only includes one who seems to be Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Ḥayy. The influence of ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī on the latter is starting to show.

Let us listen to the dialogue section of za‘lān lēh with ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī’s biṭāna, then with Sheikh Yūsuf’s biṭāna.

(♩)

Then comes the conclusion. We will hear both performers’ conclusions when we listen to the complete dawr. Both Sheikh Yūsuf’s and ‘Abd al-Ḥayy’s conclusions are almost the same.

Let us listen first to ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Afandī Ḥilmī singing dawr El-bulbul gānī, recorded by Zonophone around 1906 on three 25 cm record sides — the smallest record size available then —.

Note the sorrow and despair in ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Afandī Ḥilmī’s performance of Yā hal tara nirga‘ el-awṭān, Wallā n‘īsh el-‘umr gharāyib, as if he were saying 'we will be estranged our whole life and will never come back'.

The dawr starts with a taqsīm performed by Ibrāhīm Sahlūn, followed by free layālī, then a dūlāb, then the dawr, then again taqsīm and free layālī. Note that he is singing to the same octave as Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī, but his performance is a bit slower, thus confirming the concept of despair present in ‘Abd al-Ḥayy’s interpretation. Also note how ‘Abd al-Ḥayy exploits the recording technology. In the third side, he uses the turning of the disc in order to shift to the ṣabā and the bayyātī he performs to the rāst fifth scale step.

Let us listen to ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Afandī Ḥilmī.

(♩)

Beautiful, Sī ‘Abd al-Ḥayy…. Beautiful!

Three years later in 1909: the first thing we notice is the evolution of the recording technology. We will note that Sheikh Yūsuf had rehearsed this dawr with his band, had sung it hundreds of times, and that the band had played it hundreds of times. They had recorded it many times until the time to stop and the time to continue came naturally. The recordings are devoid of mistakes or flaws, or of the voice of the sound engineer asking them to stop. None of these problems exists.

Everything is clear because the path was followed more than once. Sheikh Yūsuf wants to convey that he is singing this dawr in an exceptional way, different from the way others perform it, and the band is obviously helping him in this.

Sheikh Yūsuf recorded it on four 30cm record sides. The durations of Sheikh Yūsuf’s recording and ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī’s recording are different.

As to the rhythm, Sheikh Yūsuf sings it faster than ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī. He starts with a dūlāb followed by layālī to the bamb with Muḥammad Afandī al-‘Aqqād’s taqsīm. The layālī to the bamb are fixed/prepared as it seems that he is prepared to convey happiness and hope. He goes up to very high octaves. The happiness and joy are prepared for. He starts the dawr directly when the layālī to the bamb end. The end of the dawr is synchronized with the end of the fourth side.

Let us listen to Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī.

(♩)

Beautiful Sheikh Yūsuf… beautiful!

Honestly, I am moved and experience great ṭarab when I listen to ‘Abd al-Ḥayy.

In this dawr, we notice the father’s authority of Sheikh Yūsuf who in all his works says: 'if you want to sing this dawr, it must be performed this way. And if you want to sing the qaṣīda, the qaṣīda is performed this way'…. He is not a performer who cares about nothing in this world and wants to sing just for the sake of singing, such as Abd al-Ḥayy. Sheikh Yūsuf’s ever-present father’s authority served him well in this dawr as it added tenderness, hope and happiness to the singing of a musical text he could have interpreted with despair and sorrow like ‘Abd al-Ḥayy.

I do not like to say whom I would rather listen to, yet I honestly prefer Sheikh Yūsuf’s version of this dawr, not Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī’s.

We have reached the end of today’s episode of Sama‘ .

We will meet again in a new episode, with another musical text to analyse.

Sama‘ is brought to you by AMAR.