Images

All images are courtesy of AMAR Foundation

search

All images are courtesy of AMAR Foundation

Music in Yemen (2)

The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents Durūb al-Nagham.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of Durūb al-Nagham.

Today, we will resume our discussion on Music in Yemen.

We had stopped at the Rasulid dynasty and music during the Rasulid dynasty.

It seems that Yemen was happy and prosperous during this period.

Yes.

Yemen was almost unified. The Rasulid dynasty ruled over North Yemen, the Western Tihāma regions, and the city of Aden, and benefited from the commercial sources and activities in the city of Aden and its port. It grew richer and was able to attract civilisation aspects as well as specialized professionals. It also became rich by imposing taxes on Aden’s commercial guilds.

Classical, religious and folkloric music prospered during the Rasulid dynasty. But, did the end of this dynasty lead to the end of this boom? Did Yemeni music enter a phase of decline?

Fortunately not, since the Rasulid dynasty was followed by another dynasty born on the heights of Yemen, the regions around Sanaa: the Qāsimiyyīn, imams of the dynasty of Banū Qāsim who were Zaydī imams, and completely different from the Rasulid dynasty. They established their reign upon the end of the Ottoman occupation of Yemen, i.e. the end of the 16th century and beginning of the 17th century.

The family of Zaydī princes, Bayt Sharaf al-Dīn, who were a political elite as well as a cultural/intellectual elite, practised ḥumaynī poetry in a very distinctive way, notably Muḥammad Bin ‘Abd al-Lāh Sharaf al-Dīn, an author who lived in the 16th century during the Ottoman occupation. This great poet gave a great push to poetry and to music during this period. His poetry still exists today: it was recorded in the period’s manuscripts. Remarkably, Muḥammad Bin ‘Abd al-Lāh Sharaf al-Dīn compiled his ḥumaynī dīwān and added to this work numerous historical stories, such as his own biography, offering extensive information on his era and his art, as well as on how he excelled in the art of poetic writing and in inshād, added to glimpses about music during this period.

What about the melodies?

Unfortunately, the melodies were neither recorded nor notated — this only started in Turkey shortly after this period. On the other hand, they were recorded in the 20th century.

We compare the melodies with the qaṣīda in order to try to find out the age of these very old melodies, most of them dating back to this golden age when most poets were also composers.

Yes.

Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Lāh Sharaf al-Dīn was probably a composer himself. Many of the melodies we know today were very possibly composed by these great 16th and 17th century’ poets.

Indeed. Because, ‘Alī Ufuqī Bēh’s Turkish manuscripts, for example, include some Arabic melodies that are still sung today. He notated them then… Even though we have memorized them orally, not through his notation. So these pieces may have been indeed transmitted orally over 400 years.

It is indeed possible and, furthermore, does not imply that this heritage did not evolve: the melodies we hear today were certainly not exactly the same then. These people undoubtedly played at the time a major role in establishing this heritage we know today.

Nevertheless, the musical system remained faithful to itself.

I do not think that the musical system changed a lot because, as you know, Yemeni melodies are influenced by the Arabic and Zalzalian vocal steps. But the theoretical maqām system does not exist in Yemen. Consequently, I think that the oral vocal legacy transmitted these musical scales as they were, while the melodies probably changed or were improved…etc. Yet the musical system did not change a lot.

What about after Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Lāh Sharaf al-Dīn? We have almost reached the 16th century…

The 17th century’s authors include Aḥmad al-Ruqayḥī. The 18th century’s authors include great poets with strong texts, such as ‘Abd al-Raḥmān al-Ānisī, who lived at the end of the 17th century and beginning of the 18th century.

During the Qasimid dynasty?

Yes. Towards the end of the dynasty… ‘Abd al-Raḥmān al-Ānisī and his son Aḥmad al-Ānisī, another great poet.

Their poetry still exists?

Yes, their qaṣīda still exist, along with the related melodies, even though we are not sure if they were composed then or later on.

Are there any names of famous musicians from this period?

Unfortunately not, possibly because of the fundamentalism during the Zaydī Qasimid Imamate or the negative social opinion on art. But there are names of great artists starting the beginning of the 19th century.

Such as?

The poets who further developed ḥumaynī poetry were mostly from the 18th century, including ‘Abd al-Raḥmān al-Ānisī and his son Aḥmad, and ‘Alī al-‘Anisī — a judge, they called Judge ‘Alī al-‘Anisī. All their qaṣīda are written down in manuscripts. They mostly developed the Yemeni muwashshaḥ that includes 3 parts:

The bayt; the tawshīḥ; and the taqfīl.

This sectioning seems to have musical implications: a very important element in order to write Yemeni music, since, when we hear today a full melody with its 3 parts — the bayt, the tawshīḥ, and the taqfīl —, we know it is an original melody, because it is very difficult for any artist to affix such a melody onto another qaṣīda… This demonstrates how the History of Literature helps Music History.

They are linked.

Very closely linked indeed. And a great effort is required to study these forms with precision.

Can they be named muwashshaḥ ḥumaynī?

Yes. To Yemenis, the muwashshaḥ is a form of ḥumaynī poetry.

Is there a recording of a muwashshaḥ authored by one of these poets?

Yes, there are many. The famous ones include Yuqarrib al-Lāh lī bi-al-‘āfiya w-al-salāma made of 3 parts, and sung by many artists.

Its author is unknown?

Its author is ‘Abd al-Raḥmān al-Ānisī himself, the father.

In whose voice will we hear it?

We will listen to it in the voice of Sheikh ‘Alī Abū Bakr Bāsharāḥīl, accompanied by the Yemeni ‘ūd, i.e. the ṭarab or qanbūs.

When was it recorded approximately?

Around 1939 by Odeon, in Aden…

(♩)

We have completed the 18th century phase, and the muwashshaḥ with its 3 parts.

You mentioned that names of musicians started to appear from the beginning of the 19th century. Why is that? Did Yemen open up to the rest of the world? Did something happen in Yemen on the musical scene? We have now reached another Ottoman phase, haven’t we?

Yes exactly. This historical element is essential to understand such issues: the second Ottoman occupation of Yemen started in 1870 in Sanaa and ended in 1919. These 50 years were very important for Yemen as they are behind its scientific and cultural openness. Art in Yemen was encouraged as the Ottoman rulers and soldiers in Yemen enjoyed Yemeni music: certain Yemeni artists sang and played at the governor’s mansion, or in the homes of Ottoman officers.

There is an important point that is not mentioned enough in History: many officers were of Arab origin.

Of course.

They were either from the Levant or from Egypt, which explains the interest and mingling between the Ottoman officers and the Yemeni artists, poets, or people in general.

The first artist whose name was mentioned and whose biography was known is Jābir Rizq, born in Sanaa around the 1870s, who practised his art but later left Sanaa and settled in Tihāma where he did not resume his musical work but joined a Sufi order and became a poet more than an instrumentalist. On the other hand, he may have authored qaṣīda and composed many melodies. His musical journey only lasted a few years.

He did not record of course.

He did not indeed.

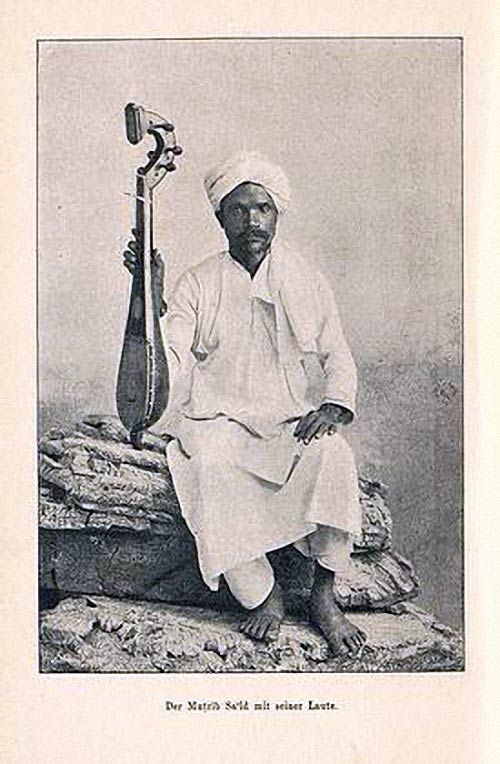

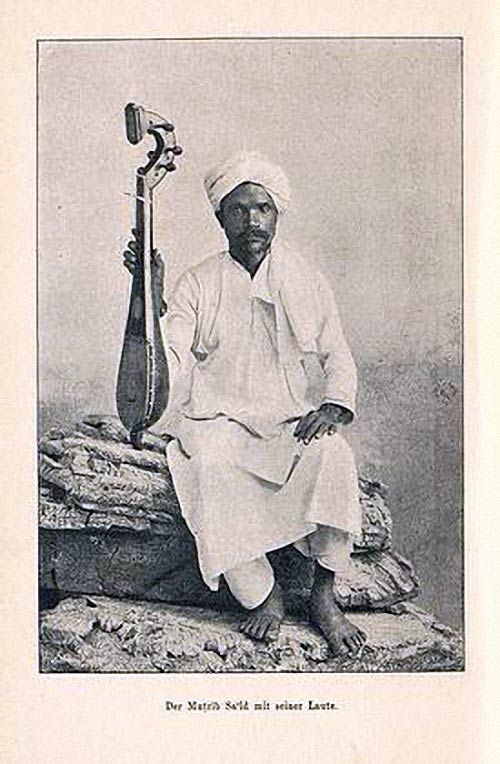

He was followed by a major artist, Sa‘d ‘Abd al-Lāh, who played the qanbūs or ṭarab for the Ottoman officers, and who lived at the beginning of the Imamate in Sanaa since 1905: a hard period because of the wars between the Zaydī imams and the Ottoman occupiers, during which the artists were swinging between the Ottoman authority that encouraged music, and the Zaydīn who did not. Thus, their position on the social, religious, and political levels was difficult, as described in the biography of Sa‘d ‘Abd al-Lāh who, as an artist, was accused by Aden’s jurists and fundamentalists of contravening the religious system, and of drinking alcohol. His ‘ūd playing was also subject to accusation. A beautiful legend tells how he faced these accusations, and how, thanks to his art and his mastery of religious qaṣīda, he regained the respect of the imam by performing religious qaṣīda and even some religious prayers accompanied by the ‘ūd. Which allowed him to resume his art under the rule of Imam Yaḥya Ḥamīd al-Dīn. Yet his position remained complicated and he was killed, probably by fundamentalists, in the early 20th century.

And we do not have any recordings of him.

This artist had numerous pupils: some remained in Sanaa and practised the art of singing, while others travelled to Aden including famous ‘Alī al-‘Aṭṭāb and Muḥammad Ẓāfir who fled from the fundamentalist Zaydī rule and moved to Aden in the early 20s.

Aden was under English authority.

Indeed. And practising art was permitted there.

So, Sanaa singing was divided into two parts: a part in Aden and a part in Sanaa.

And the Aden part is the one we have recordings of.

Their recordings date back to the late 30s, while the recordings made in Sanaa started later than the 50s.

Which one of Sa‘d ‘Abd al-Lāh’s pupils shall we listen to?

We will not listen to Sa‘d ‘Abd al-Lāh’s pupils because they did not record either. Yet, their pupils in Aden did, including Sheikh ‘Alī Abū Bakr Bāsharāḥīl whom we heard performing qaṣīda Yuqarrib al-Lāh, and Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Lāh al-‘Antarī who lived, practised his art, and made recordings in Aden. These are the two geniuses who recorded in Aden in the 1940s.

Let us listen to something in the voice of Al-‘Antarī…

We will listen to Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Lāh al-‘Antarī performing qaṣīda Riḍāk khayr min al-duniā wa-mā fī-hā accompanied by the big ‘ūd as he did not play the qanbūs…

(♩)

Wow.

Let us now move from the historical aspect to the theoretical aspect.

Let us talk about what reached us from the melodic system and the rhythmic system in Yemeni music, and about the ṭarab, i.e. the Yemeni ‘ūd, its tuning types, and whether it was tuned to a maqām or had a fixed tuning, and also talk about the sources confirming the above.

Let us start with the ‘ūd because it is a good theoretical introduction to the musical structure in Yemen.

Note that most theories in most books on Arab music and to the Arabic musical system, until a late date, presented the ‘ūd as the instrument onto which the theory could be applied.

Indeed. And this also applies to Yemen.

We mention the Yemeni ‘ūd, i.e. the ṭarab or qanbūs (we repeat these words to satisfy all our colleagues because there are different words, and there is a difference in the appellations).

Some fight because of these appellations!

This ‘ūd has 4 strings, unlike the oriental ‘ūd, known in the 20th century and that has 5 strings. The 4 strings are similar to those of the oriental ‘ūd except for the fifth string, i.e. the first, the second, and the third strings are Do Sol Re.

You mean from the jawāb to the qarār.

Yes. The qarār is the fourth string, but it is tuned to Do, not to La like the big ‘ūd. It is the jawāb of the first string.

The zīr answers the bam.

Yes.

Three strings are double strings and the upper string is a single string. Is it the same in all qanbūs?

Yes.

Does the single string change the tuning?

Usually, it does not. But the tuning to Do is very important because it is considered as a confirmation of the jawāb.

It is used a lot in playing even if the melody is not to the Do maqām/scale.

It is just there…

Yes.

But why is it a single string? Is there an explanation?

Because it is big, and made of iron or brass.

This is why it is big.

Just like the fifth single string on the big ‘ūd.

Considering these 4 strings, the Do can be a qarār to the rāst maqām, and the third string can be a qarār to the bayyātī maqām, and the third one, plucked, would be a Mi / sikāh.

Most Yemeni melodies are built upon this basis: their structure is Zalzalian, whether they are to the rāst, to the bayyātī, or to the sikāh. There are derivatives, but these can be considered original. A Si bemol is never played to the bayyātī, it is always the Si demi bemol. This is the basis of the Yemeni melodic system.

I will not tackle the subject of maqām because there is no theoretical knowledge of maqām and their appellations in Yemen. Yet those who know them can distinguish them in the Yemeni melodies without citing these names.

So, there are no maqām names.

No. Neither are there names for notes or scales.

Only the strings of the ‘ūd have names:

- the first one is the ḥādhiq (energetic);

- the second one is the awsaṭ (as it is approximately in the middle)

- and the rakhīm.

The rakhīm…

The beautiful appellation rakhīm came from some qaṣīda that tell about the ṣawt rakhīm (melodious voice) of the birds or of the ‘ūd.

The fourth string is called jarr or yatīm (orphan).

The yatīm maybe because it is a single string.

Yes, it is a single string.

These are the only melodic elements we have concerning Sanaa music.

What about the rhythm?

The rhythm, on the other hand, has more appellations, almost 10.

There is also a compound form, with many rhythms, named qawma: a suite of at least 3 rhythms, 3 melodies, and 3 songs.

It could be called a waṣla.

Yes, it could be called a waṣla. This waṣla usually starts with the das‘a built upon the aqsāq rhythm, either 7/8 or 11/8. It can be sung as follows… (♩)

This was the 11/8 das‘a.

It is followed by the wusṭa, 4/4 or 8/8 depending on the notation.

Such as…?

… (♩)

This was the wusṭa, followed by the sāri‘ that has almost the same rhythm but faster, which causes the pattern to change a little, as follows… (♩)

This was the sāri‘.

These 3 forms make up the traditional Sanaa waṣla compound form, i.e. the qawma, an old appellation for an old Arabic poetic form. Yet, the qawma’s concept can also be similar to the nawba’s.

There is only one song for each rhythm?

No. And this is where the difficulty starts. Yemenis usually affix different lyrics to the same melody, or different melodies to the same lyrics.

It is like a national pastime…

Consequently, the relation between the melody and the qaṣīda is not stable, and makes things very difficult on the Historical level, as we must assume that the melodies we are hearing did not accompany the same lyrics in the past, and that the lyrics we hear today were not sung with the same melodies, and furthermore may have changed many times after they were authored. See?

Oh!

The evolution of music in Yemen in the 20th century and the advent of recording somewhat settled things. Today, we know that, for example, a certain qaṣīda was sung to a certain melody by a certain artist, in 1940, recorded by Odeon on a certain date. But we do not know at all how it was before the recording era. This is an important characteristic of the oral heritage: it is not fixed and settled and transmitted from generation to generation as we may think it is. It is a sea that flows from a generation to another with all its forms, types and variations.

Are these related or separated by something similar to mursal melodies or improvised qaṣīda?

Yes of course. This also applies to non-muwaqqa‘a melodies. Yet, when listening to a non-muwaqqa‘a melody, one may discover its relation to a muwaqqa‘a melody, for example Wa-mugharrid bi-wādī el-dōr …(♩)

This one is not muwaqqa‘a.

…(♩)

This one is muwaqqa‘a. Have you noticed the difference?

Yes.

The same melody can also be applied to a 11/8 rhythm for example.

The same melody, but a different mudūd.

I can deduce that they did not improvise a lot on the muwaqqa‘ form or the mursal form, such as in music in Egypt and in the Levant.

No, especially that they do not have the notion of maqām. They do improvise some elements, but this improvisation is not built upon the notion of maqām, such as modulating from a maqām to another, or the variation within a sub-maqām to an original maqām … all these do not exist in Yemeni music.

So improvisation is the re-interpretation of the same melody.

That is how it is in Yemeni music.

We have learned a lot about music theory in Yemen, about the rhythm and the melody.

We will talk in our next episode about the musical forms in Yemen.

We have reached the end of today’s episode of Durūb al-Nagham.

We thank Prof. Jean Lambert for the valuable information and precious recordings.

We will meet again in a new episode.

Durūb al-Nagham.