Images

All images are courtesy of AMAR Foundation

search

All images are courtesy of AMAR Foundation

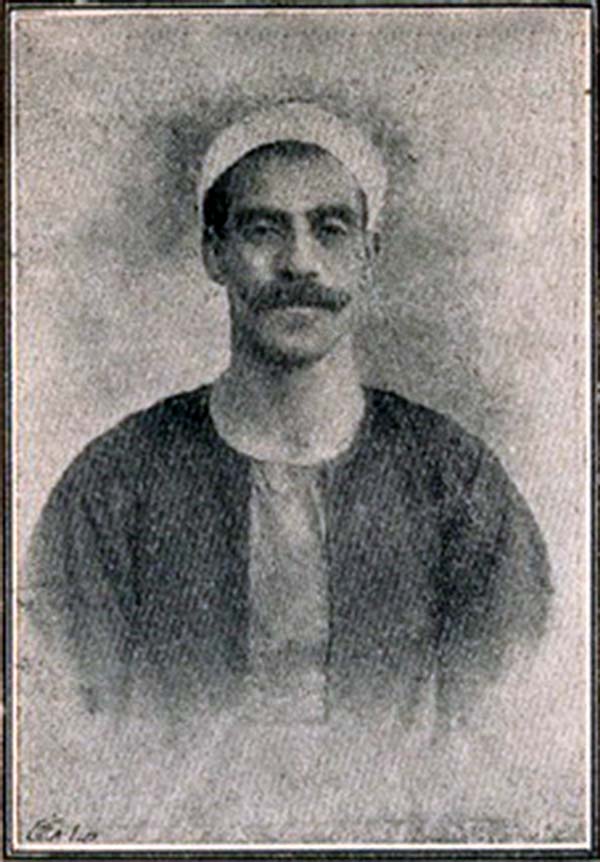

Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī (1)

The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Today, we will be talking about Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī.

The “trustworthy muṭrib”.

The “trustworthy muṭrib”.

Who gave him this nickname?

God knows… Who was it?

Adham al-Jundī’s son Aḥmad al-Jundī claimed that Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī was nicknamed the “trustworthy muṭrib”.

Since Aḥmad al-Jundī is of the generation following Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s generation, should we believe this statement?

First and foremost, we must understand the meaning of trustworthiness in performing dawr… We will discuss this later on.

Our guest Prof. Frédéric Lagrange, who needs no introduction and who participated in many of our episodes, will be talking to us today about Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī.

Let us start again.

Where did the “trustworthy muṭrib” nickname come from?

The only sources that mention Sayyid al-Ṣaftī are Syrian sources. Early 20th century Egyptian sources barely give any valuable information about him.

Kāmil al-Khula‘ī mentioned him.

Indeed. This is why I said “barely give any valuable information”.

Later on, Adham al-Jundī’s book as well as his son Aḥmad al-Jundī’s book “Ruwwād al-Nagham al-‘Arabī” include a brief paragraph on Sayyid al-Ṣaftī. These sources being of Syrian origin indicates that Sayyid al-Ṣaftī often visited Bilād al-Shām in the early 20th century and that he made a significant impact in the region, to such a point in fact that the only sources existing today that mention him are Syrian sources. Still, the information may be wrong since they include serious errors from the start, such as stating that he was still a Sheikh working in the biṭāna of Sheikh Ibrāhīm al-Maghribī in 1904 while we know that he was among the pioneers of commercial recording starting 1903.

I saw cylinders records of him.

Let us start again.

Is the name “al-Ṣaftī” a surname or is it…

…related to a region?

This name either refers to the village of “al-Ṣaft” under the jurisdiction of Ṭanṭā or to the village of “Ṣaft al-laban” in Imbābā that was separate from Cairo at the beginning of the 20th century. We do not know if the name “al-Ṣaftī” implies that he was born in al-Ṣaft village close to Ṭanṭā or in Ṣaft al-laban in Imbābā, or if is it just his surname. The only indication that he may have been from Ṭanṭā is that he studied under Sheikh Ibrāhīm al-Maghribī who was himself from Ṭanṭā.

It seems that Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī started off as a munshid: the second indication is the information mentioned in al-Khula‘ī’s book “Al-Mūsīqī al-Sharqī” published in 1904 or 1906 –depending on the edition– about Ṭanṭā’s Sheikh Ibrāhīm al-Maghribī, stating that al-Maghribī composed for Sufi orders especially on the occasion of the Mawlid Nabawī, and that he taught muwashshaḥ to Sheikhs, namely Ismā‘īl Sukkar, Sayyid al-Ṣaftī, among other faqīh.

A pleasant anecdote mentions that in the mid-20th century, people thought that the tawshīḥ ḥarīrī was named as such in relation to Darwīsh al-Ḥarīrī –which may be true–, and that the tawshīḥ maghrabī was old and came from the Maghrib –which is wrong since it was named as such because it was composed by Ibrāhīm al-Maghrabī.

Ibrāhīm al-Maghrabī or Ibrāhīm al-Maghribī? …Then it must have been Ibrāhīm al-Maghrabī. Maghrabī was his surname and bears no relation to the Maghrib.

It seems that Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī was more versed in wazn than all the other muṭrib of his generation, especially those who recorded muwashshaḥ at the beginning of the 20th century. This appears clearly when comparing the muwashshaḥ recorded by Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī, ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī, and even Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad with the version recorded by Sayyid al-Ṣaftī.

First, Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī is the only one who recorded muwashshaḥ in full, unlike al-Manyalāwī or ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī who only recorded extremely abridged versions of the muwashshaḥ. Sayyid al-Ṣaftī performed the muwashshaḥ in full, i.e. as written in the books published at the beginning of the 20th century.

He sometimes recorded them on a full disc, not just on one side.

Furthermore, Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī did not always dedicate a full record-side to the performance of a muwashshaḥ that only constituted an introduction before the dawr or the qaṣīda, or any other section…

(♩)

Salāma Ḥigāzī also performed an abridged version of the muwashshaḥ before going directly to qaṣīda “Badru ḥusnin lāḥa lī” for example.

The one he interprets before “ ‘Alayka salāmu al-Lāh yā ghazālan”.

“Yā ghazālan ṣāda qalbī” …exactly.

‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī, Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī, and Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad performed muwashshaḥ composed to the aqsāq or to the samā‘ī thaqīl, i.e. relatively short wazn, unlike Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī who was inclined to record and perform muwashshaḥ composed to much longer and maybe much more complicated wazn.

Muḥajjar, awfar, shambar, nawakht …etc.

This is his particularity.

Also, comparing in the catalogues of early 20th century discs the number of muwashshaḥ recorded by muṭrib shows that the percentage of muwashshaḥ recorded by Sayyid al-Ṣaftī is very high compared to the others. Moreover each muṭrib specialized to a certain extent in a certain style that was his specialty, a style that was particular to him and for which he was famous. All muṭrib sang dawr… Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī sang a greater percentage of qaṣīda, while Sayyid al-Ṣaftī specialized in muwashshaḥ.

This in itself poses a question, a strange issue, a riddle: we know that all the early 20th century muṭrib, to be allowed to sing in public concerts, had to pass the taḥzīm test –described with Sāmī al-Shawwā regarding instrumentalists, or with Prof. Al-Ḥifnī concerning muṭrib– that included a significant number of muwashshaḥ and to distinguish maqām as well as wazn. Thus, they were all versed in wazn –even complicated wazn. So how do we explain the existence of a current that preferred abridged interpretations of muwashshaḥ and of another current, almost exclusively represented by Sayyid al-Ṣaftī among all the other first class takht muṭrib, that was not well-liked by the other singers? Why did they avoid or neglect the muwashshaḥ form?

We will never know if this was limited to the recorded versions or if it also concerned live performances.

Indeed…

Yet discs reflect, even though unclearly, the musical reality between the beginning of commercial recording in 1903 and World War 1, a period during which the record industry could not change the rules and impose itself in the musical milieu, nor dictate to muṭrib, music professionals, instrumentalists and the whole industry, what to sing and what to record…etc. We are referring to the beginning when, if most muṭrib sang muwashshaḥ and if muwashshaḥ had played a significant role in concerts and within the waṣla, it would have been reflected in the recorded waṣla. Thus, the scarcity of muwashshaḥ in these recordings reflects a certain reality, though maybe not the whole reality but still the dominant form in the first ten or twenty years of the 20th century.

Shall we listen to a muwashshaḥ in the voice of Sayyid al-Ṣaftī?

The most beautiful muwashshaḥ recorded by Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī include “Ḥill ‘ala al-astār” and “Ḥayyara al-afkār Badrī”.

And “Ghuḍḍī gufūnik”.

And “Ghuḍḍī gufūnik” to the maqām ṣabā.

To the 19-pulse’ ḍarb awfar, and “ ‘Unq al-malīḥ”

Let us listen to the full muwashshaḥ waṣla in the voice of Sayyid al-Ṣaftī.

(♩)

Dear listeners,

We have reached the end of today’s episode of “Min al-Tārīkh” dedicated to Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī.

We thank Prof. Frédéric Lagrange.

We will meet again in a new episode to resume our discussion about Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī.

“Min al-Tārīkh” is brought to you by Mustafa Said.