Images

All images are courtesy of AMAR Foundation

search

All images are courtesy of AMAR Foundation

The Qānūn Musical Instrument 1

The Arab Music Archiving and Research Foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents Durūb al-Nagham

The qānūn is a trapezoidal string instrument played by plucking the strings with two plectra fixed to both forefingers with a ring called kushtbān. The qānūn has 26 courses of strings, most of them with 3 strings, except for a few 2-string courses. It has been a central instrument in the Arabic takht — i.e. the traditional music ensemble performing vocal and instrumental waṣlāt in the Arabic Orient — at least since the Nahḍa (Arabic Musical Renaissance) which started in the mid 1800s. We have little evidence on the usage of the qānūn in previous centuries and we do not know precisely when it adopted its present shape. We only know when the ‘arabāt (mandals) were implemented. Yet, a number of qānūn instruments displayed in museums worldwide date back to the 16th century.

The name of this instrument: qānūn (meaning rule, norm, principle) designates in this context the principle of melody as it is the only musical instrument in the oriental takht that can play all the notes on open chords without resorting to thrusting. Additionally, there is no relation whatsoever with Pythagoras’ scale named qānūn that Al-Fārābī mentioned in his Kitāb al-mūsīqī al-kabīr ("The Great Book of Music").

The parts of the qānūn:

1.The ṣundūq al-ranīn (resonance box or sound box): the main part of the qānūn, usually made of walnut wood, with a trapezoidal shape and a right-angled corner.

2.The wajh (soundboard): the wooden top covering the resonance box, above which the parallel courses of strings are tightened.

3.The qibla: the smaller base of the resonance box

4.The ka‘ b (foot): the right-angled side of the resonance box with holes forming triangular groups of three where the strings are fixed.

5.The misṭarat al-malāwī (pegs ruler): a ruler-shaped wooden piece fixed to the left side of the box with numerous holes — between sixty three and eighty four but mostly seventy eight holes.

6.The malāwī (pegs): the tuning keys.

7.The anf (nose): a wooden stick fixed on the bridge connecting the resonance box to the pegs ruler, with numerous string slots in groups of three.

8.The raqma: a wooden frame whose width covers more than half the qibla’s length, and length covers entirely the qānūn’s width. It is divided into four or five parts each called kayla on which fish-skins are stretched. They serve as sound amplifiers.

9.The faras (bridge): triangular wooden stick with its base fixed on wooden holders fixed to the fish-skins, i.e. raqq al-kayla in its centre.

10.The rakīza (base): an ivory — or wooden, today – quasi-trapezoidal part with its bigger base fixed to the qibla, and the smaller base holds the faras.

11.The shamsiyya: the openings on the surface of the resonance box.

12.The ‘arabāt (mandals): added metallic latches or levers fixed to a wooden ruler next to the nose — implemented in the late 19th century in Turkey. They can be raised or lowered by the qānūnist with his left hand in order to change the pitch. Their numbers vary depending on the chord and on the qānūn, according to the required result.

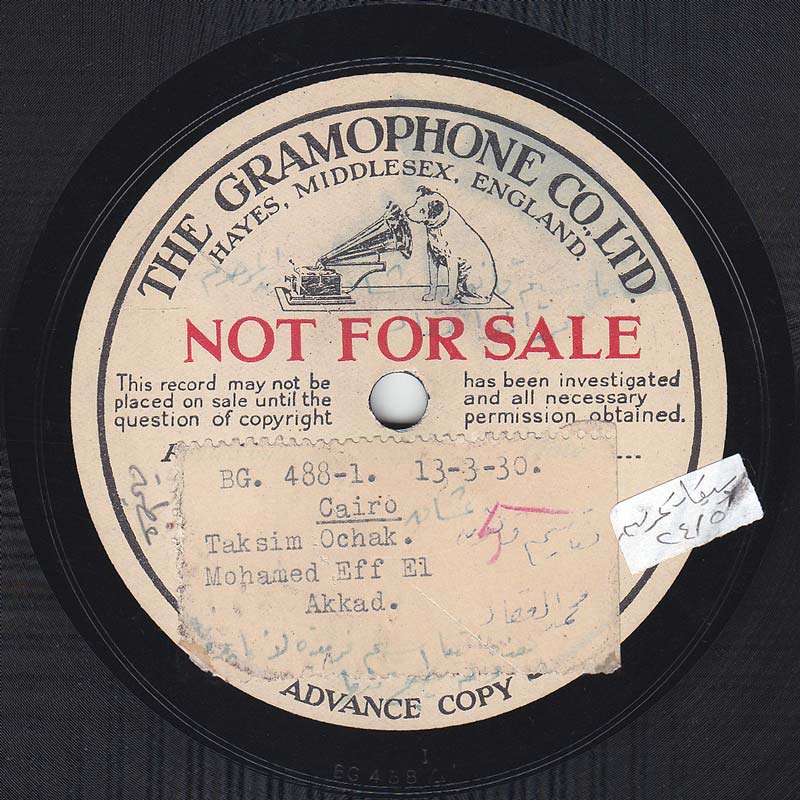

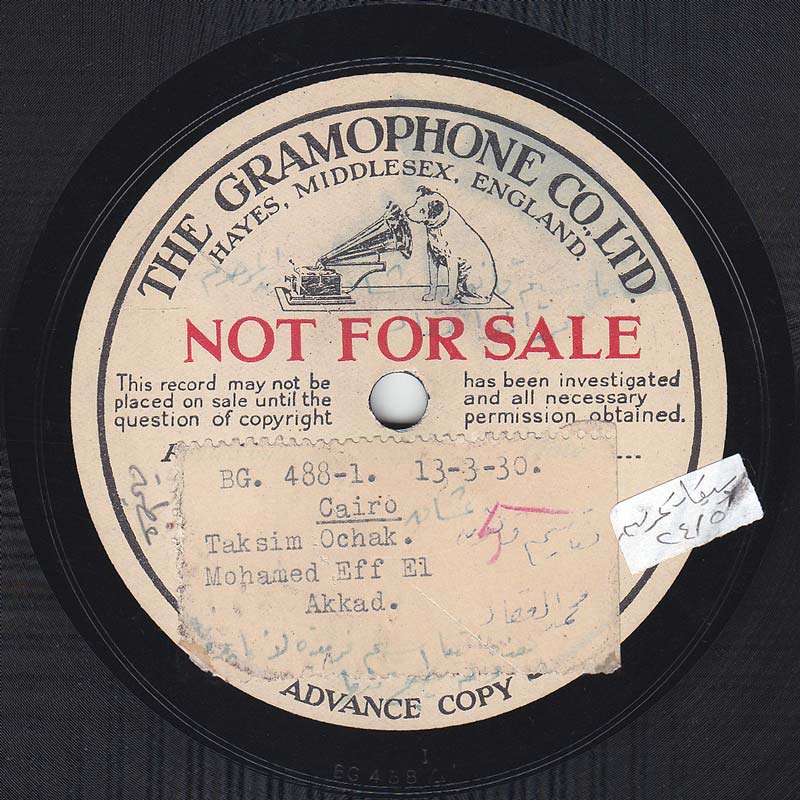

Muḥammad Ibrāhīm, taqāsīm sīkāh, Zonophone daughter company of Gramophone, around 1906, order # X 102960, matrix # 7810100

We will listen now to the first khāna and lāzima to the bashraf rāst, performed by ‘Āṣim Bey, recorded by Gramophone in 1914, order # 18309 18310, matrix # 2523 Y and 2524 Y, performed by Takht Al-‘Aqqād. The purpose of listening to this record is to highlight Muḥammad Al-‘Aqqād’s playing. We can hear two sounds produced by the qānūn (bass and treble). This implies that the musician is using both hands equally (the right hand for treble and the left hand for bass). When we hear one sound produced by the qānūn synchronised with a maqām shift, the left hand then thrusts the strings on the left end of the course.

Let us also listen to unpublished taqāsīm ‘ushshāq mursala (of non-metric measure) by the same musician, recorded by Gramophone in 1930, matrix # BG 482

We will listen now to an old samā‘ī bayyātī performed by Takht Al-Shawwā in which ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī played, and recorded by Polyphone around 1930, order # V 50642, matrix # 578 BN. Note the difference in playing the qānūn between the different khānāt: rāst, ḥijāz, and ṣabā. Each khāna includes a specific pitch shift, played using the ‘afq thrusting technique.

Now, let us listen to taqāsīm ḥijāz recorded by Odeon around 1926, order # X 47944, matrix # EX 2844. Added to the beauty of the taqsīma, ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī was one of the best qānūnists during this period. He mastered the technique of ‘afq, a talent showcased more than once in this recording.