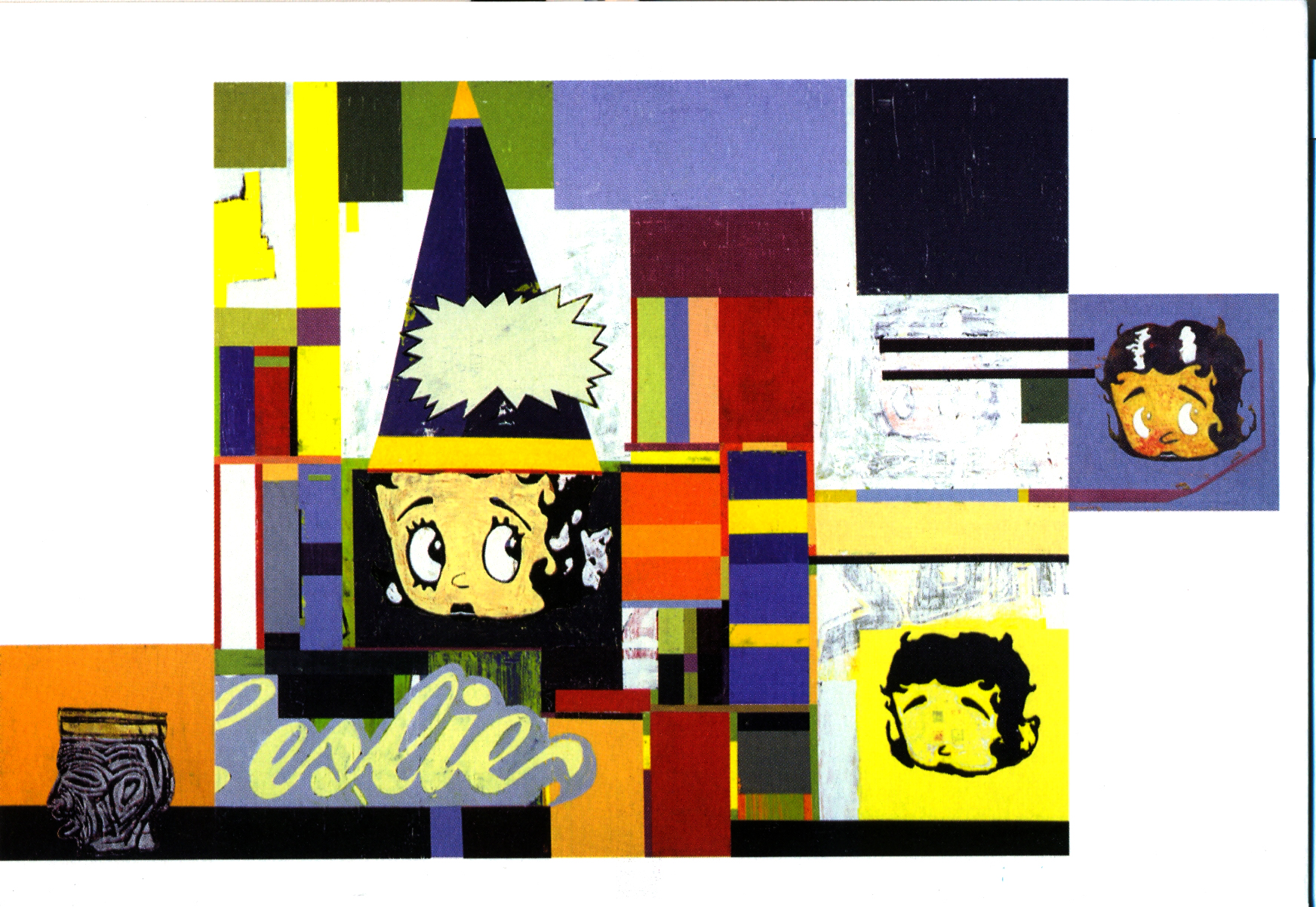

Lulu, 2001

Demian Flores Cortes

Lulu, 2001

Oil on canvas

search

Demian Flores Cortes

Lulu, 2001

Oil on canvas

Demian Flores, Sparkling Syncretism.

From the very start, the art of Dernian Flores (Juchitan, 1971) has been expressing the complexities of cultural mestizaje. In his constant commuting between Juchitan and Mexico City he has woven an intricate network of references and analogies between the istrneria tradition of his homeland and the urban environment where he grew up and became an artist. As a hybrid product, his work reflects his concerns about the survival of Zapotec roots in a world increasingly homogenized by an ali-encompassing globalization.

His recent paintings chronicle a reality that is pervasive nowadays in Mexico: the loss of identity resulting from a media invasion. If, during the 16th century, the Spanish and Mesoamerican cultures fused through the systematic destruction of the Indian past, ever since the middle of the 20th century, we have witnessed a different sort of colonization. It has been achieved by a relentless bombarding of images broadcast from the Western cultural centres towards its periphery - specifically from the United States to the south. Besides the overwhelming effect of electronic media on the most remote areas of Mexico, in regions like Oaxaca there has been a profound infiltration of American culture via the innumerable migrant workers that travel north of the border in search of better opportunities. They frequently return entranced by the mirage of the 'American Way of Life'.

Demian is himself a migrant to the country's capital, and has become a sharp observer of these socio-cultural phenomena. In his recent works he brings about a visual synthesis of what he sees as a road to alienation and an identity crisis. The acculturation processes by which Oaxacan communities get westernized strongly impress Derman In fact, he has been the only artist to dwell on these topics. Perhaps for that reason, keen critic Robert Valerio called him "the young dissident of Oaxacan art." From the outset, Flores developed a personal style based on expressionistic drawings.

In previous works, Demian was already scrutinizing the ways in which Zapotec culture expresses itself and communicates meaning. He was already transforming Indian imagery as an expression of syncretism that has been gaining strength in the people's way of portraying themselves. At this point, his iconic repertoire includes images emblematic of the pre-Hispanic past and of local and imported popular culture. With those images he constructs a pointed synthesis of expressive forms and techniques that give shape to his very own perceptions of time and space. He thus features the dilemma of assimilating foreign elements and deforming local forces through a dialectic process of alienation and appropriation. In order to do this, he employs an urban post-pop language and makes use of the mechanical procedure of serigraphy-transposition onto the canvas, which is a technical variation on what Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein did as founders of 'Pop Art'.

Demian mixes shock images and, through iconic deconstruction and decoding, he poses the relevance of cultural symbiosis. This confrontation of images that gain power in the synthesizing process simultaneously addresses the perceptive and the conceptual orders. Demian has completely abjured the formal saturation that characterized his previous work, a horror vacui that emerged from the juxtaposition of superimposed scenes in an infinite series of translucent layers of painting. He has evolved from a Baroque style to a sort of sober minimalism. According to the artist, the way in which space is organized in these canvases directly alludes to Monte Alban, one of the best laid-out cities in Mesoamerica. His compositions are now open and airy, and his fine, elegant and almost ethereal figures float in a space devoid of reality, over a background totally covered in golden hues that generates eerie feelings similar to those experienced in mystical trances.

In all these paintings, metaphors work as conducting threads, while at the same time referring to ancient traditions. Gold, considered the most precious of metals due to its solar, regal and divine character, is a sign of absolute perfection. It is worth remembering that in pre-Hispanic mythology it was the gods' excrement, fertilizing the earth as it fell upon it, and thus helping along the continuance of the cycle of nature. The colonial culture of the New Spain was itself branded by golden sparkles. It gave great impulse to the creation of wood altarpieces covered with gold leaf, and of estofados (multicoloured gold-burnished wood figurines) as sublime offerings to God. Gold also makes us think of Monte Alban's treasure: the richest legacy of gold jewelery handed over from our pre-Columbian past. The sparing use of elements and the absence of color givf' additional depth to Dernian's works, whose strength lies in their serial imagery distributed in arbitrary planes that are oblivious of perspective or scaling.

The pictorial discourse of Demian Flores has become more concentrated and focused. His voice is intent and direct, and his images are purposeful and convincing. He confirms Robert Browning's

dictum: "Less is more."

Germaine G6mez Haro

New Findings at Monte Alban.

1. The Facts.

Demian Flores Cortes embarked on a new archaeological quest in the mythical city of Monte Alban. With enormous courage he faced the great solar observatory of the Central Valleys, and Iounr, insurmountable obstacles and undecipherable signs that failed to stop him in his search to reveal the mysteries hidden within the walls of the great city. Demian then came back with the body of work that made up his latest exhibition: Monte Alban, a show that can technically be divided into two interrelated thematic series.

In his preliminary ventures, Arena Mexico and Arena Oaxaca, Demian Flores had explored the worlds of wrestling and urban graffiti. He put them forward in highly baroque canvases whose visual foundation was Hindu iconography in as much as it integrates human bodies and architectural elements in search of a private nirvana. These canvases contrasted with his very direct serigraphy work stamped on bags and packages of different sizes. But Demian has now made up his mind to face a pre-Hispanic wrestling match from the ahistorical disposition of our age.

II. The History.

During the Second Period (Epoca II), Monte Alban was dominating a great part of the Central Valleys as a result of an economic and political evolution that allowed it to colonize and incorporate other communities. During that era an evident occupational development was reached, signaled by a clear differentiation of social strata: rulers, ball players, warriors, noblemen, priests and sorcerers, plus masons, quarrymen, ceramists, sculptors, goldsmiths, astronomers, painters, full-time craftspeople devoted to stonework and of course food producers. At this point the State returned to ancient traditions and developed a strong ideological apparatus based on a coercive polytheistic religion. Its underlying concept was to relate social organization with the forces of nature that, being untamed, were positioned as anthropomorphic gods. It was thus that Church and State were not two individual entities, but an indivisible one.

"Religious rites included incense offerings, self-sacrificing and sanctification rituals like tongue a and earlobe bleeding, human and animal sacrifice, and extremely complex ceremonies for burials, 3 especially for those of the nobility, warriors and priests. They also performed ceremonies, involving inebriating beverages, hallucinating mushrooms and tobacco, in which children, women, slaves and prisoners of war were sacrificed. These included dancing rituals that lasted for several days and nights." (Enrique Fernandez Davila and Susana G6mez Seraffn, "Arqueologfa y Arte, Evoluci6n de los Zapotecos de los Valles Centrales, Perfodo Formative" in Historia del Arte de Oaxaca, Arte Prehispanico, Vol. I, Oaxaca, Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca- Instituto Oaxaquefio de las Culturas, 1997, page 102).

III. The Exhibit.

Contemporary television is a showcase of nameless savagery. The titles of many TV shows might as well appear in posters promoting an itinerant circus, and that does not even include the day-to-day bombardment of news broadcasts. The former programmes are private-world peep shows directly descending from tabloids that nobody reads anymore. The latter are war dispatches from a public circus that we are forced to contemplate in dread because they are live pages from history. Row Upon row of indelible images get embossed in our minds and might well fascinate the future practitioners of Dr. Freud's craft.

Demian Flores Cortes starts this time from a small, key problem: What sacrifices must we offer hl ~U nch the vengeful thirst of our new tutelary gods? On a daily basis the mass media try to incite new communions to satisfy themselves, but possibly a more effective and secretive answer is the one that this artist exhibits at Monte Alban.

In order for us to understand the accessing code, we must start - as always - at the end, which j also a beginning of sorts. The first batch of paintings is a bridge connecting the present to the works of Arena Mexico. The saturation of the pictorial field forces the viewer to find the protagonist and solve the riddle of its iconic relationship with the rest of the painting, in order to establish the narrative plot that gives meaning to the work.

The central piece here is Of rend a Propiciatoria, which contains all the elements of the series. It is the natural link between this phase and the previous paintings, and maintains a fragile balance between baroque excess and the need to polish the expressive elements of the Monte Alban series. In this triptych, Demian Flores puts forward the elements that Frederic Jameson lists as premises for postmodernism: irony and schizophrenia giving rise to the ahistorical bent of the prodigal image bank.

This painting features a pyramid as a sacrificial centre where an eagle devours an image of Popeye. Meanwhile in the basement, several images struggle against a blueish stuccoed surface that we assume belongs to the pyramid. It is thus that the artist presents a scene on the foreground and suggests what might be happening on the walls. This sensation is heightened by the two small canvases that frame the main one: a secret map to find corn and a veiled hom mage to Piet Mondrian.

Three works bear the saturation of Demian's previous works: Pentimento, Tumba 7 and Carda Libre, which are built as Hindu mantras. Each internal image points to a centre that must perforce be the yearned-for vacuum. Carda Libre is connected to the world of wrestling, American comics and also the findings of abstract painting. The other two canvasses though, look like the mural paintings that were executed for the palaces housing Zapotec warriors and nobles. The Hindu structure is still there, but the characters are now national heroes, anonymous citizens or pre-Hispanic figurines. The golden and silver hues, or the sombre black give the composition a dark and epic disposition.

In Gallo Giro, the painter uses a Mondrianesque referent as pictorial support: the stripes of primary colors show us some dancers performing before the sacrifice of the two women standing at the left side. Later their heads will float from left to right, and their bodies will be taken away by the bus bearing the painting's title that is also transporting modern furniture.

Demian Flores had been perfecting the dramatic and narrative weight of the protagonists of this great codex-like work till he reached an intermediate stage with two works: Lulu and The Incredible Man. They are both examples of contemporary graffiti that can be glimpsed on the road leading from Oaxaca to the sacred city. But something happens here that irritates us. These are not commercial billboards, but images presaging sacrifices and offerings. That woman can be promoting a soda but her head is darkly afloat and tethered to something. Next to her, some ball players stand ready to play. In the second one we do not tina the hero preaching his worn out sentence, "Serenity and patience, Soloim ... " We see two srnal] heads snowing contrasting emotions on their faces. One of the last pieces, pointing where the road is leading to, is Tributo, where there is a figure holding Bugs Bunny's head, while at its side we find Memfn Pinqiifn (that most disconcerting of Mexican comic-book characters) defecating. The red color surrounding the first figure suggests the blood of sacrifice, while the yellow field on the second one points to the gold leaf that is the most conspicuous trait of the main series: Monte Alban.

Parts 1, 11, & 111 of text by Carlos Aranda Marquez.

Sharjah Biennial 6