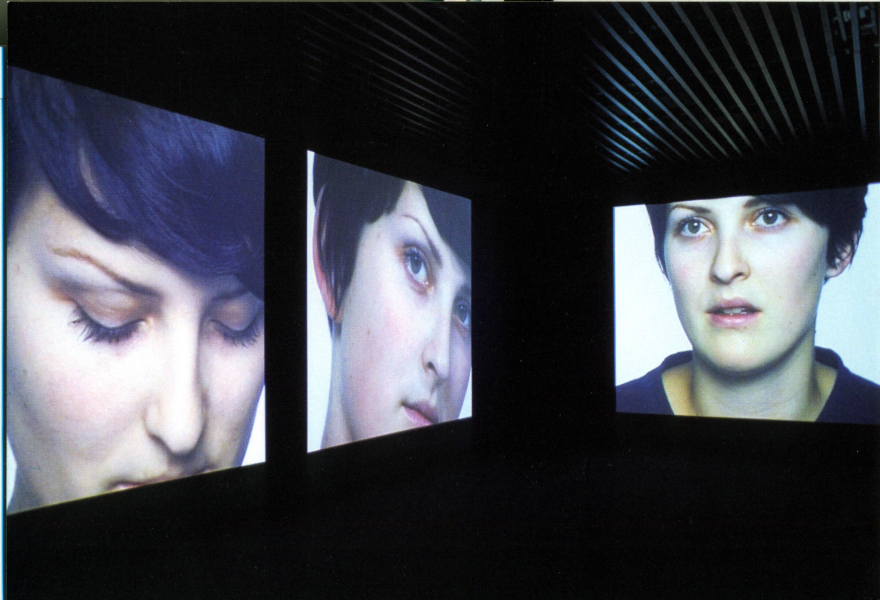

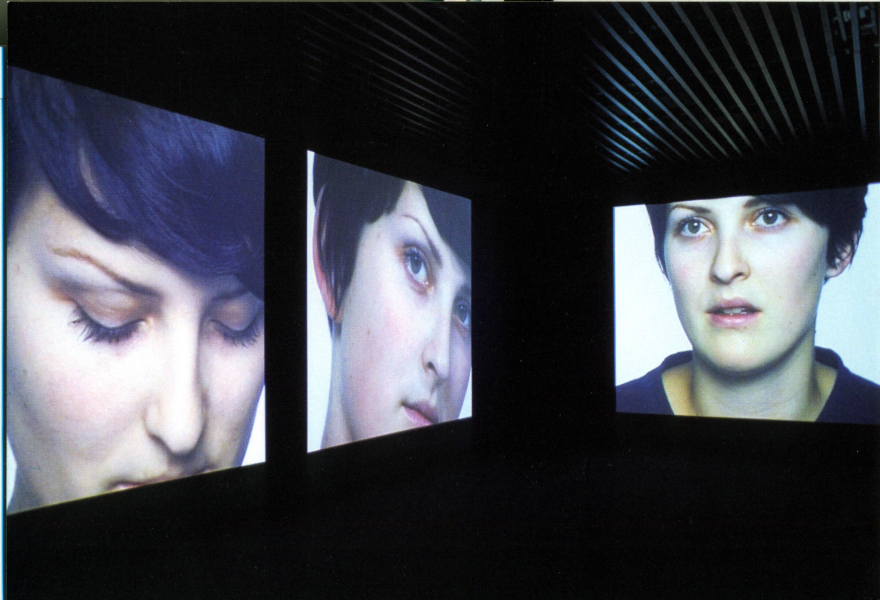

Eyes Wide Open, 2002

Ann Lislegaard

Eyes Wide Open, 2002

Three channel video installation with sound

search

Ann Lislegaard

Eyes Wide Open, 2002

Three channel video installation with sound

"When I would talk with one of my friends, I was conscious that the original, the unique portrait of her individuality had been skillfully traced, tyrannically imposed on my mind as much by the inflections of her voice as by those of her face, and that these were two separate soectectes which rendered each in its own plane, the same single reetitv.!"

Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past.

Ann Lisiegaard's video and sound works incite a heightened consciousness of perception. In her installation Eyes Wide Open (2002), she shatters the convention of the portrait as a single, still image by creating an environment of multifaceted audio and visual information. By recording her subject's movements using a video camera, and then segmenting the footage into stills, Lislegaard invites us to create a composite from a series of images projected onto three screens. The effect is one of watching three slide shows alternating at slightly different speeds. Each sequence depicts the small, inconsequential movements of a young woman a tilt of the head, a lifted arm, a shift of the gaze. Occasionally, brief blips of real time action interrupt the progression of stills, revealing their source as moving imagery, and jarring us into the present.

From time to time, the stream of visual fragments comes to a complete halt. Empty of imagery, the screen emits only darkness. A voice suddenly emanates from somewhere behind the projection a woman describing another woman. As if we have been temporarily blinded and are being aided by a seeing friend, the voice describes the other woman's movements and appearance in short, hushed phrases and streams of single words. Description is a process of selection, and therefore contains an inherent lack. Lislegaard's black segments allude to that lack as they insinuate something unseen. As in the experience of closing our eyes and trying to recall the objects in the room around us, the voice alternately frustrates and confirms our visual memory and powers of observation. It also evokes moments of synaesthesia - the production of a mental sense impression by the stimulation of another sense - by compelling us to "see" actions in the emptiness of the darkened screen. As the spoken statements mirror our process of seeing, the images on the otl1er screens reflect what we hear.

It is uncanny how a small movement by a stranger can allude to the presence of an intimate; how we are able to recognize a friend in an instant from a distance, out of the corner of our eye. Lislegaard's serial pictures echo these moments of recognition, as they flash in front of us and then flit away. Even the layered, fragmented structure of her installation mimics that of memory. However, sometimes recognition proves an illusion, and the identity we assigned someone mistakenly, revealing the blurred line between perception and cognition, the shadowy area in everyday experience that continually pervades Lislegaard's work.

Our senses, especially seeing and hearing, help us to navigate the world around us. The catalysts for seeing and hearing - image and sound - can easily be recorded and thus seemingly dislocated in place and time. Lislegaard uses streams of such recorded information to create complex sensory environments that gently, yet firmly, demand that we slow down and concentrate. As she probes and overwhelms our senses, she amplifies our awareness of our perceptual processes. Her video Nothing But Space (1997), a silent double-sided projection of blended and contorted images of an interior space and various people walking through it, both mimics and frustrates optical perception. Other works such as Corner Piece - The Space Between Us (2000) combine recorded voice-overs, flashing light and constructed architectural elements such as walls and floors to invoke the power of spoken word to alter space and conjure imagery. Conceptualized as a portrait and based on an exploration of visual and audio parity, Eyes Wide Open marks the first time lislegtJard has combined recorded imagery with recorded voice.

Many of Lislegaard's presentational tactics in Eyes Wide Open, such as the serial organization of imagery, the temporal dislocation of the viewer through recording technology, and the paring down of visual and audio information to promote ambiguity and an awareness of space, find parallels in art and film nistory. By reducing each of her audio and visual elements into elegant, simple components, Lislegaard renders her installation accessible. It is the phenomenological experience of the work that makes it complex. Art historian and theoretician Hal Foster has observed that Minimalist art "complicates the purity of conception with the contingency of perception, of the body in a particular space and time." 2 Similarly, by weaving together her reduced, divided elements, Lislegaard creates an absorbing installation charged with anticipation, sensuality, and ambiguity that confronts us with our own presence in relation to the work.

Through the sequencing of her still imagery, usteqaaro implies the fluid real time movements of her subject. This practice of dissecting motion using photography finds an early precedent in the Animal Locomotion studies of Eadweard J. Muybridge. Between 1884 and 1886 Muybridge produced over 20,000 printed plates depicting animals and humans in motion. As his subjects performed simple actions, such as bending over, walking, and dancing, Muybridge used multiple cameras to record their movements and displayed the resulting photographs in gridded, segmented rows. Lislegaard likewise uses photography as an agent of revelation, uncovering details of posture, shape, and expression normally hidden within the continuum of real time.

Lislegaard reconstitutes her subject's movements at a pace much slower than that of our usual cognition. Her freeze-frame stop motion recalls video works made by Bill Viola, such as The Quintet of Remembrance (2000), in which his subjects' real-time actions are slowed so that they appear, moment to moment, stilled. The extended duration in both Viola's and Lislegaard's work has the effect of endowing with significance their subjects' tiny movements and nuances of body language. As our brain anticipates the progression of action, our eyes are able to explore recesses of optical experience that might otherwise be missed.

Stylistically, Eyes Wide Open echoes early silent films such as Carl-Theodore Dreyer'S The Passion of Jeanne d'Arc (1928), which punctuates flickering imagery with black screens containing simple, pared-down sentences of text. Lislegaard's images and text, however, are nonlinear and autonomous. They do not function as narrative, but rather compel us to bridge gaps between image and language extracted from an endless loop of ambiguous meaning. As a sequence, the movements and moods the stills reveal are not dramatic; the woman curls her fingers, tilts her head, IJ1JiHle£ her arm, her facial expressions are not gratuitous. The voice-over is equally mundane, limited to simple, descriptive phrases such as "she is looking down" and "her hair is dark." Conceptually, Lislegaard's descriptive methodology is allied to filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard and Chantal Ackerman, both of whom allow the camera to linger over banal, everyday moments and scrutinize trivial details, to achieve an extended analysis of a single character. By endowing the moments of inaction with as much importance as the "actions" themselves, any hierarchy of information is effectively eliminated- In Eyes Wide Open each frozen moment is as important as the one preceding it, which is as important as the ambient voice.

Lislegaard carefully edits her video footage into stills that are refined and subtly emotive, highly conscious of the fact that each small shift of her subject's gaze and posture can reveal a vastly different temperament. Evocative of classical paintings such as Leonardo da Vinci's Lady with an Ermine (Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani) (ca. 1490), the stills Lislegaard selects contain gazes full of quiet power and gestures that are elegant in their simplicity. In one sequence, for example, the woman's hand slowly falls from her shoulder, her ivory fingers radiant against her dark shirt. Like that of Leonardo's Cecilia, her hand appears both affected and relaxed; simultaneously conveying tenderness and strength.

Shot against a plain white background, Lislegaard's subject exists in an environment seemingly devoid of depth and specific location. Her simple clothing and lack of accessories provide few clues to her identity. Such straightforward depiction with little in the way of narrative content finds a parallel in the works of many contemporary photographers. Thomas Ruff for example, creates sharp, larger-than-life portraits in the style of passport pictures that invite our eyes to meander through a profusion of detail. Similarly, Rineke Dijkstra photographs isolated teenage subjects in a straight documentary style, but complicates her seemingly categorical approach by exposing nuances of her subjects' awkwardness. Her series of portraits of the eighteen-year-old French legionnaire, Olivier Silva (2000), for example, reveals the psychological implications of posture and the potential for miniscule drifts of facial expression to be read as enormous shifts in mood. In a like manner, Lislegaard's subject seems alternately confident and vulnerable, trusting and apprehensive, implicating the intrusiveness of the camera and the inherent self-consciousness of being observed.

Lislegaard's work is immediate, intimate and sensual. The camera allows us to stare, to zoom in, to settle our gaze on close-up views of the woman's body and face.

In fact, there are three sets of "gazes" operating in the work: the artist's gaze serves as a conduit between the woman's and our own. But are we watching or being watched? The voice-over complicates our position in the work as it inevitably describes some of our own movements and attributes. As a female voice describing another woman's actions, it also mirrors the construction of the work as a portrait of a woman by a woman. The tenor of the voice is unthreatening, calm, and gentle; it seduces and envelopes us with its intimacy, inviting us to lean in and listen. In our attraction we discover an ambiguous eroticism, a condition that often saturates Lislegaard's work. In her installation ! (2001), for example, a stack of audio-visual equipment emits a slowly pulsating red light and the sound of a woman gasping repeatedly; it is unclear whether she is being continually surprised or sexually aroused. The infamous School of Fountainbleau painting Gabrielle dtctree and One of Her Sisters (1595), encapsulates the ambiguity of gesture and eroticism that fascinates Lislegaard. The act of a woman pinching another's nipple is so odd and explicit that it dominates the painting's narrative content, yet its meaning remains unresolved. Does it symbolize Gabrielle d'Estree' s pregnancy by Henry IV, or is it simply a portrait of two women in a bath, created to celebrate sensual pleasures?" As in Lislegaard's work, the meaning of the painting is open-ended, its sensuality unspecific.

Eyes Wide Open is a full-body experience that confounds perception. In this respect, Lislegaard's work draws on strategies pioneered by film and video artists in the 1960's and 1970's who used light and sound to dislocate the viewer by transforming the physical parameters of the gallery space.> It folds the corners of the room into the corners of our eyes and heightens awareness of our physical presence in the space. Our experience of the work depends on how we navigate it, and in the process we become acutely aware of our perceptual activity. Eyes Wide Open invites a wider angle of vision and a broader range of hearing. Like the minimal musical compositions of composers such as Steve Reich that use phasing manipulations to create overlapping and periodically merging rhythms, Lislegaard provides us with numerous streams of syncopated audio and visual information to which we can intermittently affix our attention. As counterpoints to the lulling rhythm of the projections and the calm tenor of the voice, the visual and audio tracks constantly interrupt, laminate, and punctuate one another-snapping us over and over into the moment.

Like grasping at a dream that dissolves as we wake up, Eyes Wide Open forces our mind to jump between two audio and visual spectacles in an effort to reconcile, process and store individual moments and impressions. The acute sensory awareness it demands deflates our passivity, forcing us to realize that reconciliation of audio and visual stimuli is a never-ceasing, solitary experience. To experience the work is to discover its essence, as Lislegaard disorients us only to push us into the immediacy of our bodies and our minds.

Sharjah Biennial 6